The Diverse Work of Melina Mercouri

by Benjamin Leonard, Best Boy

Melina Mercouri was a Greek-born actress, singer, and politician. Born in 1920 and graduating from the National Theatre’s Drama School in 1944, she spent the next eleven years performing only on the stage. In 1949 she played Blanche DuBois in the Greek production of Streetcar Named Desire and gained international fame performing the song “Papermoon”. In 1955, that fame led to her debut film in which she played the titular role in Michael Cacoyannis’s Stella (a Greek retelling of Carmen) earning a nomination for Cannes Best Actress Award. Cannes is also where she met writer/director/actor (and her future husband) Jules Dassin. He was showing Rififi, his first film since being blacklisted during the McCarthy era. The two hit it off quickly and had a long-lasting personal and professional relationship. Mercouri would be featured in nine of Dassin’s eleven subsequent films (which is about half of the films she went on to make). At the time, they were both married, but each got a divorce in 1962 and they married each other in 1966.

I watched five of Melina’s films from various points in her film career to discuss here and I will cover them in the order in which I viewed them for no other reason than I couldn’t think of any better way.

I started out with Never on Sunday (1960) which was written, directed, produced by and starred Jules Dassin.

It was released two years prior to their divorces, but it is clear that, if nothing else, Jules saw everything about his love for Greece embodied within Melina. Dassin had become fascinated by the works of Nikos Kazantzakis (author of Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ) in the mid-1950s. This, and meeting Mercouri, drove Dassin to become obsessed with Greece and Greek culture.

Never on Sunday tells the story of Homer Thrace (Dassin) a nebbish American amateur philosopher in search of the source of sorrow and Ilya (Mercouri) the locally beloved Greek prostitute who has a passion for the classic tragedies. Homer has a very American view of sex and womanhood but is intrigued by Ilya’s interest in the tragedies. He encourages her to develop her mind and leave behind the pleasures of the flesh. Initially, Ilya isn’t interested. She already has so much joy, what more could she get from delving deep into her mind? As they get to know each other longer, we learn much more about Ilya’s strength and how she helps hold together the community. She isn’t just the local prostitute; she acts as a sort of union organizer for the other prostitutes as well as a moral and cultural supporter in the life of everyone she meets. Homer, however, is blind to these values. Through a few twists and turns, Ilya sees value in following the path Homer has laid out, but it’s all part of a scam perpetrated by the local head of crime to keep her from meddling in his control over the other prostitutes. All is eventually found out and Homer learns that Ilya (and humanity) is happier with an appreciation for the cerebral but a passion for life, love, and the arts. Homer’s philosophy needs people like Ilya and their flaws in order to exist and have meaning. In this, Melina is sly, smart and sexy. Of the films I watched, Never on Sunday shows the greatest amount of range for her and highlights her ability to carry an entire film with her charm and wit.

I followed that up with A Man Could Get Killed (1966) by Owen and Neame, which is a silly little spy-romp with some pretty cruddy love stories. It features James Garner as an unintentional spy dropped in Lisbon to take over for his recently deceased predecessor. Directly after arriving, Garner attends the dead man’s funeral and meets his girlfriend played by Mercouri. It turns out Garner will be taking over as her boyfriend as well. I love Garner and Mercouri, but there is no chemistry here, not physically or emotionally. The movie is filled with intrigue, bumbling, and confusion but is lacking in humor and charisma. Unfortunately, nothing seems to click. The story lacks any strong motivations to keep you interested in the characters or events and neither Mercouri nor Garner are given a chance to shine.

Next was Once Is Not Enough (1975) by Guy Green and based on Jacqueline Susann’s novel. I’d call this one Once Was WAAAAAAY Too Much, but that has nothing to do with Melina. In short, this is a film about a young woman (Deborah Raffin) and the way she plays out her daddy (Kirk Douglas) issues with a disgusting old man (David Janssen). Just about every character in this film is base and deceitful, at best. The only exceptions are the woman (Alexis Smith) that Douglas marries for business and convenience and her girlfriend (Melina Mercouri). These women are quite blunt about who they are and their intentions.

Mercouri probably only has about ten minutes of screen time in this film, but those few minutes are the only time I could feel a bond with any of the characters. Her character is a throwback to her role as Ilya in Never on Sunday. Her humor and passion are there for everyone to see. Of historical note, the film features a rare lesbian sex scene with older women. At the time, Smith and Mercouri were in their mid-50s. The scene is mostly tactful and makes sense compared to the rest of the film which is a jumbled mess with less tact than a drunken uncle at the holidays. (See Silvestre M. Bare’s article on Barbara Hammer for further discussion on the representation of older lesbians in cinema.)

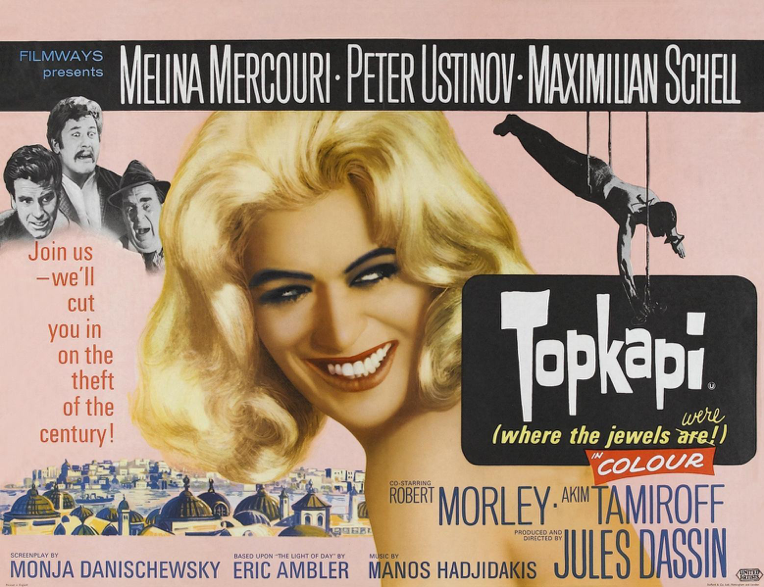

I returned to viewing Mercouri’s roles in Jules Dassin movies with Topkapi (1964), a jewel heist movie in the tradition of the original Ocean’s 11 (1960). It features a rag-tag group of inexperienced thieves that have been brought together to steal a jewel encrusted dagger from an Istanbul museum. Mercouri and Maximilian Schell are the only professionals. They are working with amateurs in the hopes that they will draw less attention from the authorities.

This is one of the few of Dassin’s later films that he didn’t write, and I think that comes through pretty clearly. Mercouri and Schell split time pretty evenly in the first half of the film, but when it’s time to pull the job she all but disappears. When she is on-screen, she owns it.

Her duties in the group are planning the job and beguiling stooges. The main stooge is a conman (Peter Ustinov) that they con in to doing their dirty work. Mercouri and Ustinov have a good chemistry and comic timing and their scenes carry the movie well. In addition, this is a visually interesting movie. The opening credits are pretty trippy and psychedelic, one heist scene involved dropping in from the ceiling by a cable that was almost directly lifted for Tom Cruise in Mission:Impossible more than thirty years later and there’s a huge carnival that features public wrestling matches and large crowd scenes.

In general, heist movies aren't exactly my thing. They can be fun but they tend to spend more time than I appreciate setting up the heist when, in the end, you know it’s gonna come apart at the edges and they are just gonna have to improvise anyway. This movie does follow that model, but it remains entertaining throughout most of it.

I finished my set with The Rehearsal (1974). This one was an exceptionally personal piece for Dassin and Mercouri. In 1967, a militaristic dictatorship took over Greece. They publicly spoke out against it and Mercouri’s citizenship was revoked and their property was confiscated. They continued to speak out but when the Athens Polytechnic Uprising resulted in the death of an estimated 100 unarmed students in November of 1973, they decided to act larger. They made this film in the hopes of bringing the struggle to the attention of the world and highlighting the involvement of the US government in installing the dictator.

The film, itself, is rather interesting. They shot it as a rehearsal for a fictional film that they were making. This allowed them to show the effect of the story on the actors. It also, of course, allowed them to shoot it without much in the way of sets and keep the production costs low. In addition, they rounded up a few of their friends and other greek actors interested in highlighting the atrocities.

Much of the film involves people like Arthur Miller and Maximilian Schell reading letters from eye-witnesses to the events. Otherwise, much of the story is told by individuals as they step out from the chorus. Melina has some solos during the songs and does some narrating, but not much else on-screen.

The film goes in depth to tell in gruesome detail what happened to individual people and focused on the orders that the military received in order to torture the populace. Most disturbing was their instruction to threaten to rape the women to get information. Specifically, they were instructed not to physically rape them, but only psychologically. Any injuries should not be permanent or detectable.

For me, the most powerful scene was Olympia Dukakis rehearsing being the victim of this sort of torture with the other actors as the aggressors. As if this scene wasn’t disturbing enough, the director calls for a break after their rehearsal is over. The men walk away to go have a sandwich or cigarette or whatever and we still focus on Dukakis, trying to gather herself in order to be able to leave. This really allows the brutality to sink in to us as the audience. Dukakis has reportedly stated that this was the film she was most proud of.

The film is powerful and no doubt would have been effective in swaying the public to be more concerned about the dictatorship except that it collapsed four days after the film’s production wrapped. Because of this, The Rehearsal never saw a wide release.

But this film wasn’t the end of Mercouri’s political activities. Once the Junta was removed from Greece, she and Dassin were able to move back. In 1977 she became a member of the Hellenic Parliament and in 1981 she became the first female Minister of Culture. When her party, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement, were no longer the control party, she lost this position in 1989. They took control again in 1993 and she regained the position, but died March 6 of the following year due to lung cancer.

During her political career she spearheaded many programs to support developing and sustaining the arts and culture within Greece, but a lifetime goal was to get the Parthenon Marbles back to Athens from the British Museum in London. She was never successful but, following her death, Dassin continued her work in this area until the day he died on March 31, 2008.

Mercouri was clearly a strong and influential woman. I’ve collected a number of her other films in the process of writing this piece that I wasn’t able to review. I’m eagerly looking forward to watching these in the coming weeks. If you haven’t already, take a deep dive into her work. It’ll be well worth your efforts!