MOFFIE is a visceral exploration about the cost of passing

Directed by Oliver Hermanus

Written by Oliver Hermanus, Jack Sidey

Starring Kai Luke Brummer, Barbara-Marié Immelman, Michael Kirch

Runtime 1 hour 44 minutes

In theaters and digital April 9

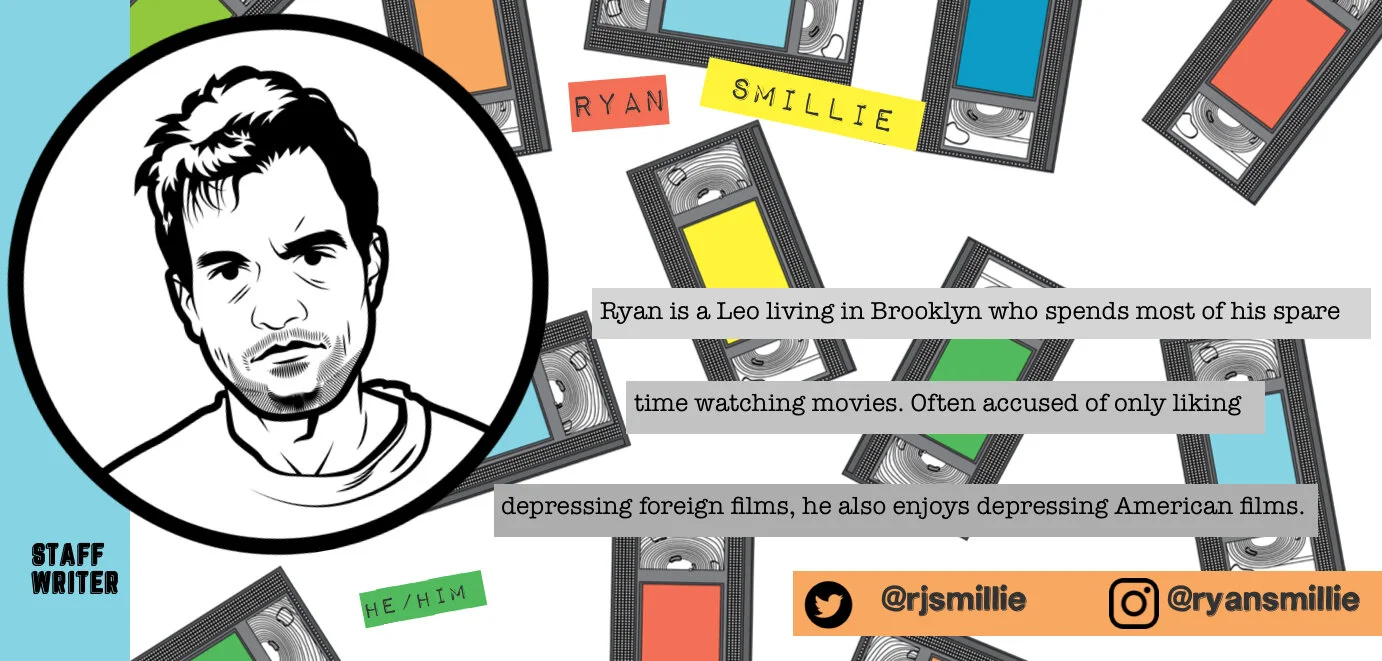

by Ryan Smillie, Staff Writer

Before closeted Nicholas van der Swart (Kai Luke Brummer) even reaches training camp for his mandatory military service in 1981 South Africa, an officer hurries him onto the train, barking orders to keep the car clean, only to piss in the toilet, and, most importantly, not to fuck with him. Van der Swart’s fellow conscripts already seem to be in open defiance of these commands, their fighting and vomiting spilling out of their compartments into the corridor. It’s not until the train stops in front of an older Black man that the young, white soldiers channel their energies in the same direction - to hurl insults and racial epithets at the man who stands helpless in front of them. Though the restrained Van der Swart doesn’t join in the verbal abuse, he’s still hanging out of the train window to watch, just like the other soldiers.

That tension between remaining inconspicuous and being absorbed operates on multiple levels in Oliver Hermanus’s Moffie. Translated from Afrikaans as “faggot,” “moffie” is a term used to denigrate South African gay men, indicating weakness, effeminacy, and even illegality under the apartheid regime. If someone like Van der Swart (or André-Carl van der Merwe, the author of the memoir from which Moffie was adapted) has known from an early age that any outward hint of homosexuality could be met with violence, then that threat is exponentially higher in the South African Defense Force (SADF). An organization devoted to upholding a brutal and white supremacist regime has no tolerance for deviance.

Van der Swart, then, seems ideally positioned to fly under the radar. He’s quiet (perhaps to a fault as the film’s protagonist), obedient, and handsome, more likely to defuse a situation than to escalate it, as we see on one of his first nights in the barracks. Though he is of English descent, his stepfather’s Afrikaner last name (which he has adopted) links him to both groups as lower-class Afrikaners butt heads with the more well-off English soldiers. An unnerving flashback shows that Van der Swart is well aware of the danger involved in even being perceived as gay, and he quickly learns that gay soldiers are harassed and sent away for torturous anti-gay “treatment.”

But it isn’t only the gay soldiers who are beaten down by the army. Hermanus takes pains to emphasize the sunburn, chapped lips and cuts that serve as physical manifestations of the military’s indoctrination. Whether the soldiers realize it or not, they’re being scarred by their time in the army, becoming numb to the brutality inflicted upon them and that they’re, in turn, expected to mete out on the Angolan border. The desert training sequences that became lyrical and homoerotic in Beau Travail are flattened and harsh here. And a volleyball scene straight out of Top Gun is marred by a shocking act of violence.

After sharing a clandestine night of tenderness with Stassen (Ryan de Villiers), a fellow recruit, Van der Swart is eager but wary to explore this new relationship. However, there is obviously no space for a budding gay relationship in the SADF, and their lightly-sketched passion erupts, of course, in a fistfight. Soon after, Stassen is mysteriously taken away, Van der Swart has no way to find him, and in no time, Van der Swart is sent off to the border. There, the tragedy and absurdity of their training is on full display. The “threat” of Blacks and communists is clearly just their existence, as the only threat on the border is the bloodthirsty SADF troops. Sachs (Matthew Vey), Van der Swart’s closest friend, has grown from temperate and reserved to violent and drunk, needing to be restrained by the same soldiers he once thought too rowdy. Even Van der Swart himself has learned to shoot first and ask questions later, killing a Black Angolan for the horrific crime of startling him.

Leaving the army, Van der Swart is clearly not proud of his service, refusing to celebrate with his mother and stepfather. However, he seems to be under the impression that he can resume his life as normal. And when he goes to see Stassen at his home, it does seem like they might be able to pick up where they left off. But once they get out to the ocean, there’s more than sexual tension between them. In addition to the societal conditioning they have to overcome, there’s the added pressure of their trauma, both physical and mental, from their time in the military, and added together, it proves to be too much. A slightly enigmatic touch calls into question whether they were even able to reunite at all, or if it was merely wishful thinking.

Either way, Moffie serves as an upsetting reflection of a historical moment that still reverberates today. In order to protect himself from the persecution that would follow from revealing his identity, Van der Swart must make himself complicit in the torture and oppression at the core of the apartheid regime. Keeping his head down doesn’t prevent him from inflicting pain nor does it keep him safe from harm himself. Hermanus’s movie could stand to flesh out its characters a bit more or to dig deeper into the political realities of apartheid South Africa, most of which are only hinted at, but it remains visceral and brutal throughout. Though the focus is on Van der Swart, it’s a tragedy for everyone involved–the young men brainwashed into a philosophy of hate and violence, the gay men forced to deny their identities or else, and most importantly, the Black people targeted simply for existing.