PORT AUTHORITY is a raw look at masculinity

Written and directed by Danielle Lessovitz

Starring Fionn Whitehead, Leyna Bloom, McCaul Lombardi

Rated R for pervasive language, some offensive slurs, sexual content, nudity and violence

Runtime: 1 hour 41 minutes

In theaters May 28, on demand June 1

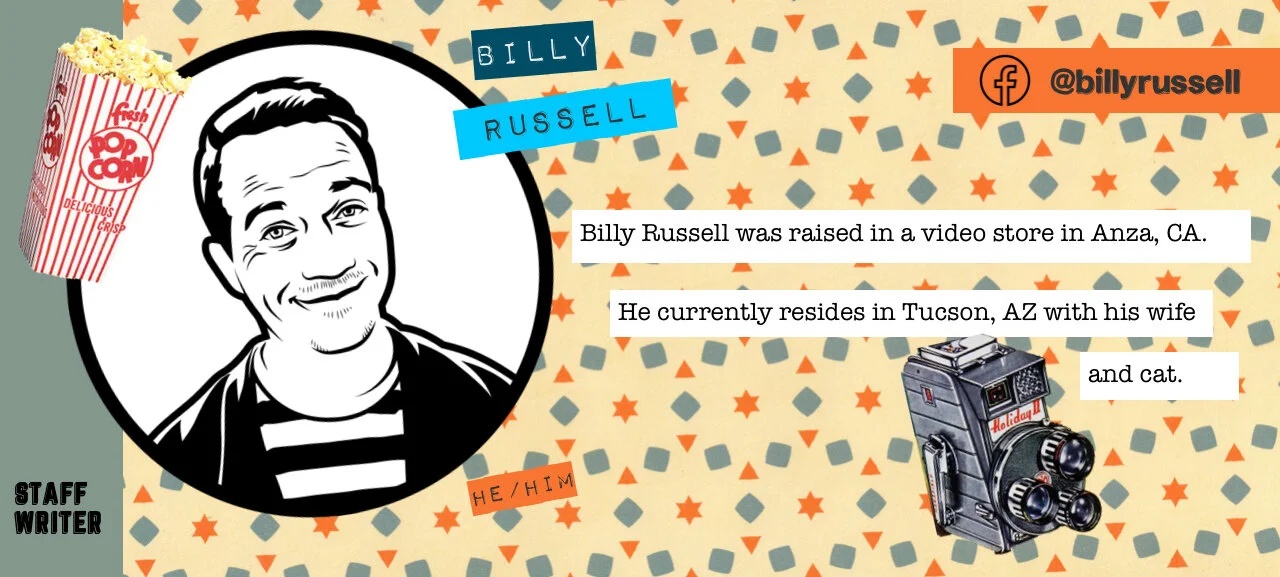

by Billy Russell, Staff Writer

Port Authority, the new film written and directed by Danielle Lessovitz, is a movie that you can feel. Many movies take place in a movie world. Most popular ones do, anyway. You know there are certain beats that are going to be hit, and the good ones do a job of emulating reality, or at least showing a version of reality, that we would recognize. But some movies, some movies just feel lived in. We understand we’re seeing a snapshot, a period of time in these characters’ lives, and they’ve lived a whole life before this and will continue living a whole life after that. The authenticity doesn’t come from years of research, it comes from curiosity. It comes from a genuine interest in seeing how these people live. It’s empathy.

It’s appropriate, then, that Port Authority gives Martin Scorsese an executive producer credit. His early films, especially something like Mean Streets, had that same lived-in feeling. It’s not appropriate to call it “gritty” even though that’s not incorrect, it’s just that grittiness isn’t the end-all result. Yes, there’s an ugliness and a threat of violence at every turn, but the grit isn’t the point. The fear of getting your eye socked in for no good reason, other than toxic men acting toxically, is a potential end-result. But the idea, why we’re all here, is in the beauty of the street-level view of life in the city.

Fionn Whitehead plays Paul, a troubled young man with anger bubbling just under the surface. It’s not that he’s an angry person, per se, but he has to be ready to use violence to survive. He’s homeless. And he’s not homeless in a quirky, “this is is personal choice” kind of thing you’d see in a movie that doesn’t really understand the cycle of poverty, like Nomadland. Port Authority understands poverty all too well. When we first see Paul, he’s arriving in the city to stay with his sister. She isn’t there. He doesn’t know where she is. When he finally tracks her down, she makes it clear that she’s not interested in helping him and he sure as hell can’t stay with her. She has no idea where he heard she was taking him in.

Paul meets Wye (Leyna Bloom) and is thunderstruck by her. He makes it his mission to get to know her. Her “family,” a house in the Ball culture scene in New York, doesn’t approve. It’s a classic tale, told simply. This young kid has to prove to the family, and to her, that even though they’re so different, they should be together. Think Romeo & Juliet, but with a sort of cinéma vérité vibe, a casual glimpse into a world as told through non sequitur dialogue, like the early works of David Gordon Green.

The movie has a villain of sorts in the terrifying Lee, played by McCaul Lombardi, but this isn’t the kind of movie that gives in to easy conventions. Lee is a monster, but he is also, at turns, generous to his friends and cares about the people he surrounds himself with. He’s a large blob of gray. He clearly doesn’t believe himself to be a monster, and the label is too simplistic. He’s an asshole capable of acts both horrifying and generous.

A major theme in Port Authority is one of acceptance. Acceptance is hard to nail down in life. Paul seeks acceptance from Wye’s surrogate family and has the tenuous acceptance of Lee, who embodies the terrifying things men are capable of. His life is a delicate balancing act, a web of lies, to avoid being alienated and there is always the looming threat of violence looming over his head. Port Authority is one of the few movies to be about toxic masculinity that doesn’t exaggerate it for dramatic effect to absurd highs. It’s shown simply as what it is.

In a more formulaic movie, Paul would have to prove his worth by entering into and winning some sort of competition. His acceptance would be won and it would be a happy ending. Port Authority doesn’t work that way. Without giving away too much, the ending is indeed a happy one, but not the one you would necessarily expect. It’s a glimpse at something that may happen one day. Breaking down barriers isn’t an easy task and it takes lots of work. Do Paul and Wye stand a chance together? Maybe. I hope so. Their attraction to each other looks and feels real and the cinematography is appropriately beautiful and the score is fantastic. There are lots of emotions in Port Authority and the movie earns them all.