SUMMER OF SOUL deftly mixes Black joy with political history

Directed by Ahmir "Questlove" Thompson

Featuring performances by Stevie Wonder, The 5th Dimension, Gladys Knight & the Pips, and Sly and the Family Stone

Rated PG-13 for some disturbing images, smoking and brief drug material.

Runtime: 1 hour, 57 minutes

In theaters and on Hulu July 2

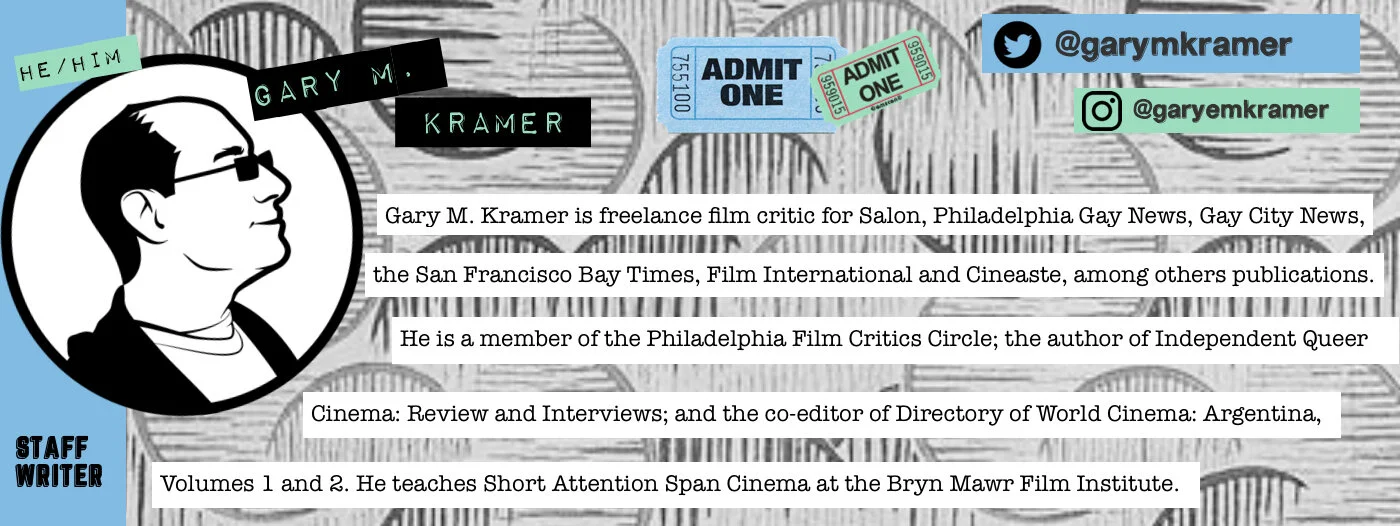

by Gary M. Kramer, Staff Writer

The Harlem Cultural Festival, dubbed “The Black Woodstock,” took place in what was then called Mount Morris Park in Harlem. The six week-long festival featured acts ranging from blues and gospel to Motown, Afro-Cuban and, of course, soul. While the entire festival was filmed, the footage “sat in a basement” for 50 years. Now, Questlove’s marvelous documentary, Summer of Soul (…Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) presents the music and messages — and it could not be timelier.

The film mixes performances, interviews with attendees and musicians, as well as archival footage and news reports to provide a socio-cultural history of the era. The “sea of Black people” — more than 300,000 folks attended the concerts— was inspiring for the performers on stage as well as the community, who in 1969 were promoting Black consciousness in the wake of the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, as well as both John and Robert Kennedy. As the film explains, the anger and rage of Black men and women was starting to boil over. The Harlem Cultural Festival provided a soothing balm for folks during this politicized time of protests, unrest, and the Vietnam War.

Summer of Soul certainly addresses the attitudes of the day, with racism, economic inequality, and drug addiction and abuse discussed throughout the documentary. A particularly telling segment has the Black community responding to the moon landing with nonchalance and disdain, insisting that the money spent by the government could have been used to help reduce poverty in Harlem.

Questlove’s film, however political, is also very celebratory and the joy felt during each concert is infectious. As one interviewee describes it, the festival was “The ultimate Black barbeque.” And when someone talks about the aroma of Afro sheen and chicken that permeated the air, viewers can almost smell it.

Summer of Soul is a fabulous time capsule for the music and fashion styles of the time. Many of the bands wore matching outfits and there is an abundance of ruffles and fringe as well as colorful costumes on stage. One performer wears a polka-dotted shirt with striped trousers which is kind of fabulous. There are brief discussions of the dashiki and “Black hair as identity,” as well as links to African heritage in Hugh Masekela’s appearance, and Nuyorican culture with Ray Barretto’s performance. (Lin-Manuel Miranda is quoted during this segment; but so too is Sheila E., who observes how Barretto uses his wrists to drum). The power of the drum to speak to people is also shown, but Questlove organizes the film like a mixtape. He lets the film pulsate to its own rhythm, emphasizing the importance of music as a force to unite, incite, and inspire — and it does.

The performances are uniformly exceptional. Watching a 19-year-old Stevie Wonder play the drums on one tune and the keyboards on another is hypnotic. The Chamber Brothers next launch into “Uptown,” and B.B. King performs a rapturous version of “Why I Sing the Blues.” And this is all in the first twenty minutes, with another hundred to go. Some viewers will be so blissed out they won’t want the film to end.

Questlove takes a moment to honor Tony Lawrence, the host and promoter who was able to pull off the event with the support of Mayor John Lindsay. Summer of Soul also reveals that the Black Panthers provided security during one concert when the police were unreliable. These tidbits are interesting, as are the discussions about the segregation of music. When The 5th Dimension perform “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In,” singers Billy Davis Jr. and Marilyn McCoo movingly describe the importance of performing at this particular concert.

Likewise, the festival’s gospel portion, which is described as “channeling the emotional core of Black people,” is quite rousing. The Edwin Hawkins Singers’ rendition of “Oh Happy Day” is crowd-pleasing, but even more impactful is Mavis Staples sharing a microphone with her idol Mahalia Jackson for a performance of “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” which is identified as Martin Luther King’s favorite song. King’s assassination is recounted here as well, in a necessary, reverential moment.

Summer of Soul does overlap interviews with musical performances which may be distracting for some viewers who want Questlove’s documentary to be a pure concert film, but the discussions are salient. Topics raised, which include Black militancy and Freedom music, are valuable and contribute to the tenor of the times.

The film hits another groove during the Motown concert, as David Ruffin dazzles by holding a high note for a good 15 seconds during his version of “My Girl.” Gladys Knight and the Pips perform, and Knight insists that the concert, “Wasn’t just about music, but about progress.” Questlove makes points about progress later in the film when Charlayne Hunter-Gault, then a New York Times reporter, recounts her insistence on using the word “Black” and not “Negro” in the paper.

Nina Simone’s performance appears near the end of the film and it is, arguably, the musical highlight. Simone commands the stage signing “Backlash Blues” and has the audience in the palm of her hand as she recites, “Are You Ready?” which galvanizes the crowd. The only other performance (the gospel scenes aside) that has such a visible impact on the audience is by Sly and the Family Stone, who cause the attendees to almost rush the stage in anticipation. It is hard to not get swept up in the excitement. As the band performs hits like “Everyday People,” and “Higher,” it is gratifying when someone acknowledges the importance of seeing a female trumpet player.

Summer of Soul captures the energy of the concert in a way that viewers will feel. Whenever the camera cuts to members of the crowd watching in awe, moving to the beat, or dancing (even in the rain), it is pure joy.

The Harlem Cultural Festival was nearly forgotten, which makes this documentary especially welcome. And be sure to stay through the credits for a sweet cookie.