COMING HOME IN THE DARK is complex and nuanced road trip-horror

Directed by James Ashcroft

Written by James Ashcroft, Eli Kent, based on the short story by Owen Marshall

Starring Daniel Gillies, Miriama McDowell, Erik Thomson, Matthias Luafutu

Runtime: 1 hour 33 minutes

In select theaters and VOD October 1

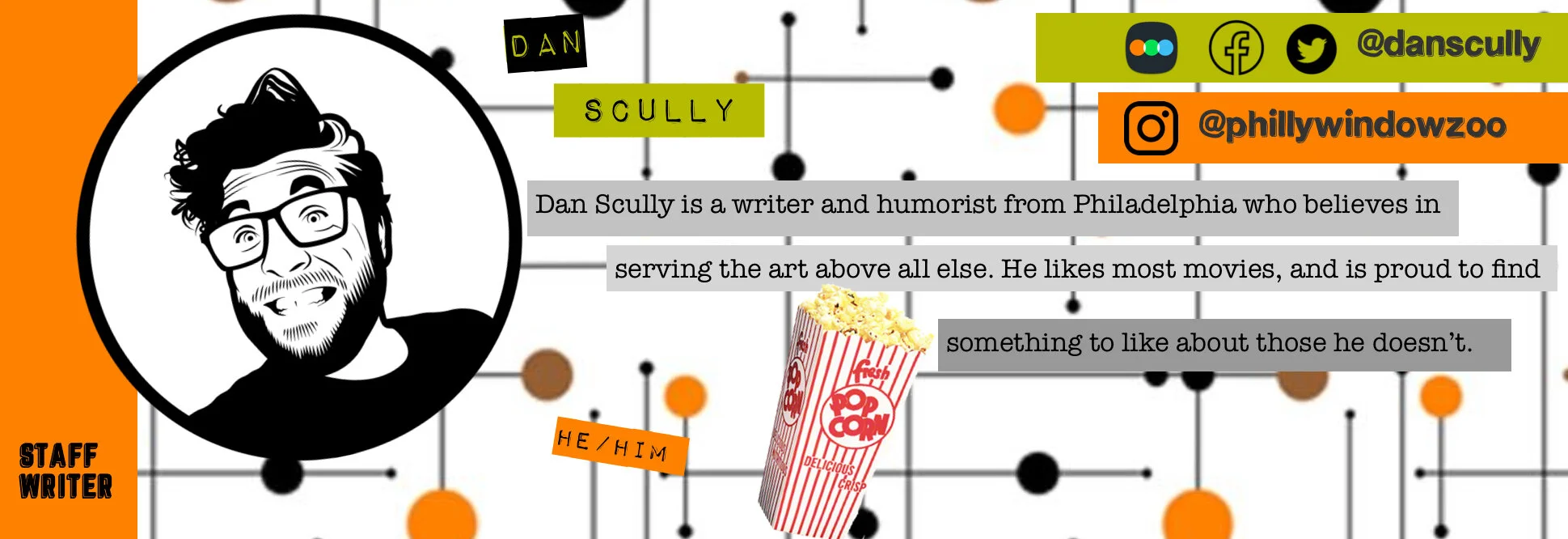

by Dan Scully, Staff Writer

“You know, later on when you’re looking back at this occasion, I think that right there’s gonna be the moment you wish you’d done something.” So says Mandrake, a sketchy drifter with a rifle on his arm and a chip on his shoulder, as he forces his hostages to wave to a passing group of strangers. A few minutes ago he and his buddy Tubs rolled up on a picnic and made captives of a family of four. His words are a chilling statement made in the coldest of blood, not so subtly alerting his victims that in regards to their current state of fear, they ain’t seen nothing yet.

And let me tell ya, they ain’t.

This particular subgenre is referred to as a “road trip” or “family in peril” thriller, and if either of those terms mean anything to you, you know what to expect. Typically, films like The Hills Have Eyes or the incredible remake of The Hills Have Eyes hit you with something hard up front — usually a bit of excessive violence — to let you know that all bets are off. Then it’s escalation after escalation, ending either in triumph for the survivors, or doom for all parties involved. It’s a good formula, and it works. Coming Home in the Dark applies the formula wholeheartedly, but don’t be fooled into thinking that the film is formulaic as a result. While the general pace, energy, and plot are all something you’ve seen a version of before, this time around there’s a compelling story behind the terror that changes everything, leading to the most aggro thriller I’ve seen since the excellent Honeydew from earlier this year.

While not outwardly gory, this is one of the most violent films I’ve seen in a long time. Director James Ashcroft keeps most of the blood off screen (or at the very least, doesn’t linger on it), but frames each sequence in such a way that I found myself frequently agape with shock. On multiple occasions I anticipated impending violence with the thought of “there’s no way they’d do something so cruel in a movie” only to be immediately proven wrong. This one goes there. On other occasions I was lulled into a sense of guarded security only to be ripped from it in a moment of sudden, blind terror. Tension and dread are not uncommon bedfellows, but so often they are made to take turns as the rhythm of “build up, release” is repeated at feature length. In the case of Dark, you can forget about release.

Most horror/thriller flicks have an obvious audience surrogate through whom the viewer can relate to the events onscreen. In the case of Coming Home in the Dark, it’s not until late in the film that it’s revealed to be about any one character above the rest, and even then it’s not the most stark elevation. While we do indeed grow to care about multiple characters throughout the course of the film (even the baddies), the strength of the narrative is not in how this horrifying experience affects any of them. It’s about the viewer, and not in that tired “why are we drawn to horror” kind of way. While I was indeed rooting for some sense of justice as the story progressed, by the time the final reel hit, the definition of justice was more than a little skewed. The lasting horror is ultimately not the memories of the nightmare suffered by Hoaggie and Jill (Erik Thomson and Miriama McDowell, both fantastic), but how their plight is mirrored by a world that, often by necessity, regularly mitigates altruism.

More specifically, what ultimately unspools here is not a black and white tale of good vs evil. Sure, there are protagonists and antagonists, but as more information about our characters’ histories come to light, loyalties shift both on screen and in the audience. These plot revelations aren’t novelty twists either — even the most shocking moments are rooted in strong character work.

Mandrake, perhaps the most complex character, played here with slimy gusto by Daniel Gillies, is a lot of the reason why the tension remains high throughout the film, in addition to the masterful balance of many spinning story plates. He is a loose cannon whose moral code is so murky that it’s hard to discern when he’s telling the truth or just playing games with his victims. Even after he’s proven himself to be a real monster, it’s easy to see why someone would fall under his sway. Case in point, his partner in crime, Tubs (Matthias Luafutu). Tubs is quiet, but capable of extreme violence, and he takes orders from Mandrake dutifully. We get the sense that this kidnapping was not necessarily Tubs’ idea, but he rarely puts up any resistance when dirty work needs to be done. Much of Luafutu’s performance is silent, his face acting circles around even the most vocal “second fiddle” villains. The relationship between Tubs and Mandrake is used to explore the idea of complicity in evil, and this exploration soon loops in the individual stories of our protagonists, granting a thematic depth that imbues even the quieter moments with a sense of oppressive terror. In a world where we all have a reason to let something awful slide, the terror struck home. I found myself looking back at all the times I didn’t do enough when faced with injustice. Nothing worse than being too late, eh?

Once again, per Mandrake: “Ya know, later on when you’re looking back at this occasion, I think that right there’s gonna be the moment you wish you’d done something.”