TIME BOMB Y2K is a nostalgic Rorschach Test about a would-be disaster

Time Bomb Y2K

Directed by Brian Becker and Marley McDonald

Unrated

Runtime: 80 minutes

Streaming on HBO on December 30

by Alex Rudolph, Staff Writer

Time Bomb Y2K, a new documentary made up primarily of news and home video footage, opens in 1999, with a very smug man sitting in some hills, saying that if we lose technology, society will return “to dust.” A woman in the same hills says she was part of her company’s Y2K security force, but got convinced the problem was too big to handle, so she broke away from society. In the moment we meet them, they are preparing animal hides for who knows what reason.

The last 23 years have turned them into a punchline, a gathering of gullible, frightened people who must have looked around on January 1, 2000 and realized they’d wasted the last couple years lecturing friends and family about a collapsing world, learning to bow hunt when they could have been more productive doing literally anything else. I still think those people are silly, but Time Bomb Y2K presents the “millennium bug” phenomenon as enough of a Rorschach test that you can see, with a little charity, the fear they could have felt. The film lacks a perspective, which can be frustrating, but it manages to present enough information that the experience remains informative and engaging.

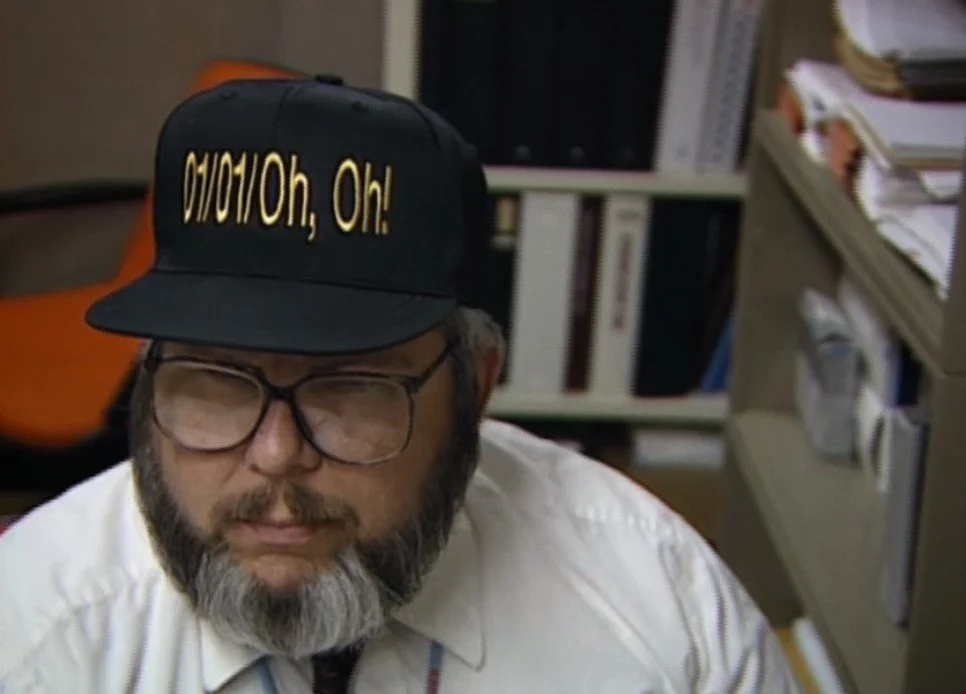

If the film has a main character, it’s Peter de Jager, the self-proclaimed “Computer Age Paul Revere.” He was the person who sounded the alarm on the millennium bug and when the movie cuts back to 1996, he’s already on news programs detailing the clearly incorrect fear that computers will flip from 1999 to 1900, rather than 2000, at midnight on 1/1/00. To save money and memory, computers’ internal calendars know the last two digits of the year, rather than all four, which was fine when 1985 became 1986, but maybe in 2000, your computer will change from 99 to 00 and think “wait a minute, computers like me didn’t exist a hundred years ago!” And have a mental breakdown that’ll take the world’s largest economies with it. “Our computers are broken,” de Jager warns. He sits for a pregnant pause before continuing: “And they will pull us under.” He’s Chicken Little, certain he’s actually Kevin McCarthy in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. He’s out here yelling about a carbon monoxide leak after merely smelling one of his own farts.

As the doom builds, as millions of computer clocks march toward a two-digit disaster, the world looks pretty good. The nostalgia trip of the way the early Internet looked and was advertised is a big part of the appeal of a movie like this to a person like me. You will see a store called "Personal Electronix," that I would give half my fingers to be able to travel back to, selling a portable television with a screen half the size of a credit card. You will see Bill Clinton and Al Gore sit in a newly Internet-capable school library, engaging in rudimentary video chat with people on the other side of the country, connection issues freezing the frame every few seconds.

The Lawnmower Man looked awful and then it looked worse and now it looks gorgeous, and I’ll gladly stare at this aesthetic for 90 minutes. There are the normal funny things that come with this kind of flashback-- out-of-context clips from the great Johnny Mnemonic, people marveling at consumer electronics that look as outdated now as bi-planes and iron lungs would have then. In a surprisingly happy moment, 1996 Jeff Bezos says, “When people look back at it, they’re going to say, ‘Wow, the late-20th century was a pretty great time to be alive on this planet.’” For many reasons, he is wrong. For many others, he is correct, though younger Bezos has no way of knowing I’m deriving joy from remembering a time when he didn’t matter to the world at all.

Later, Bill Gates tells Charlie Rose people aren’t “reliant” on Microsoft products, taking exception to that specific word in a claim that feels like denial in 2023. Some of the people guiding the early Internet were famous at the time, but few of them had the rest of us under their thumbs. Bezos hadn't yet wiped out a huge swath of physical retail, making everybody a little less social and a little more likely to have to take a job where you pee in bottles to avoid bathroom breaks you aren't supposed to be taking. The cascade of the past couple decades is clear as ever.

General computer literacy is the big difference between 1999 and 2023. Many people were excited about computers in the 90s, but few understood how they worked, which meant a few tech folks like de Jager could freak out about something and nobody you knew could prove they were wrong. Now if Elon Musk lies about his cars' self-driving features, there are plenty of people who can listen to him detail those features and say "Oh, this guy's completely out of his element and he’s talking out of his ass.”

Still, we’re shown a few regular people in regular, man on the street interviews who think the whole thing is overblown. We don't hear from any experts who say this is all overblown, which is either a failure of the documentary or a failure of the late-90s media. Books are written, expert panels descend on news magazine shows, de Jager pops up on Crossfire in a doomsday-themed tie. The host points out how much he's profiting off of the fear and de Jager gets furious. By that point, de Jager’s taken out a full-page ad for himself in the Wall Street Journal. "This is the truth, and if the truth scares you," he says, "don't shoot the messenger."

It’s a defense mechanism that can only last so long. Until then, everything accelerates until elderly women are buying solar panels and attending survivalist trade shows so that they can survive when the power grid goes down and planes start dropping out of the sky. The preparedness expo is selling blowguns and bouncy exercise chairs and features a keynote speech from John Trochmann, "the father of the militia movement." Whether the militia people are taking advantage of ignorance to get themselves in the spotlight or they truly believe they're helping is unclear, but the damage is being done. de Jager denounces those people, says he's always just been trying to raise awareness of a technical issue, but he's still wearing his custom tie as he says it. He's eventually the guy telling everybody to calm down. John Koskien, Clinton’s Y2K Czar, tells the world he’s on track to make the millennium bug a non-issue, but we’ve already seen the digital doomsday countdown clock he keeps on his desk, and things have come to the point where de Jager is joined by militias, religious fanatics and Busta Rhymes.

The week leading up to the big day, gun sales are up sharply, people are worried about domestic and foreign terrorists and an estimated 70% of Americans are stocking up on groceries and supplies. The lost and damned wait to see a Phish concert. When nothing happens, de Jager uses his final moments of fame to say this whole thing will repeat in another hundred years. The movie cuts to children in the year 2000 imagining what changes the next millennium will bring.

So what is the takeaway here? What are the directors saying with Time Bomb Y2K? A few options:

1. Peter de Jager is a grifter and the movie has presented him and his “this will all happen again” spiel as a forerunner to people like Alex Jones (Y2K:de Jager::COVID/school shootings/everything:Jones).

2. Peter de Jager was right and the movie has presented a look at a close call with mayhem, even if we now think of the millennium bug as idiotic.

3. The politicians and media were frightened about something that normal people didn’t care about and all the celebratory home video footage shows that they were correct in ignoring the government warnings. If this is the case, I don’t know why you’d release the film now, after a very real international plague killed almost 7 million people as a bunch of people ignored the government warnings.

4. There is no point of view and it’s just very fun to watch all of this old news footage.

That last bit is true— it’s an engaging, entertaining watch. I truly enjoyed it. Every other option feels a little fuzzy. The footage of children discussing the future means there's a deeper point here-- you wouldn't close on mostly off-topic footage if there wasn't-- but it eluded me, as I don't think media sensationalism, an apocalypse huckster and unfounded fears have done much to encourage or discourage any of the kids' predictions. The world moved on and the millenium bug didn't set many precedents about reporting on mass hysteria in the past 23 years. If I think of instances of large groups of people losing their minds, they seem more inspired by the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal that played out while Y2K was flaring up than by the actual millenium bug hype. But then maybe I'm one of the people Peter de Jager was worried about, standing on train tracks, sure a train isn't coming down them anytime soon. Maybe the connections are obvious. Until I realize what they are, though, I'll just enjoy this movie as a look back at a simpler, stupider time.