Re-Entering THE MATRIX: Why RELOADED and REVOLUTIONS deserve a re-evaluation

by Ryan Silberstein, Managing Editor, Red Herring

Fight Club. Being John Malkovich. Mulholland Drive. Pi. From the late 1990s through the year immediately after 9/11, many of the most popular and critically acclaimed movies challenged our conception of reality. Even surprise megahits The Sixth Sense and The Blair Witch Project called our perception of reality into question in different ways. The Matrix claims the biggest overlap between popularity and taking this idea head on, though all of these had a decent cultural footprint.The Wachowski Sisters then used the sequels to take these ideas even further by rounding out the original film with a deeply philosophical take on the cyberpunk genre.

Early on in The Matrix, Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving) is interrogating Mr. Anderson/Neo (Keanu Reeves) about his activities as a hacker:

It seems that you've been living two lives. One life, you're Thomas A. Anderson, program writer for a respectable software company. You have a Social Security number, pay your taxes, and you... help your landlady carry out her garbage. The other life is lived in computers, where you go by the hacker alias "Neo" and are guilty of virtually every computer crime we have a law for. One of these lives has a future, and one of them does not.

Since this happens early in the film, before we understand that The Matrix is an all-encompassing computer simulation, it seems to speak to the unchecked freedom possible on the internet and how it can provide an escape from the mundane everyday existence that can feel oppressive. In Neo, Thomas Anderson has developed a new identity that engages in subversive activities, breaking free of “the system” as we know it, as signified by Social Security numbers and taxes. In our waking lives, we are numbers, but in computers we can be whoever we really are (even though that is also made up of 1s and 0s, one of the film’s more subtle uses of irony).

Since the Wachowskis have transitioned, it has become commonplace to map the questioning of identity directly to gender. This book excerpt by Andrea Long Chu speaks to that better than I ever could. While that reading is absolutely valid, the film is so specific in its filmmaking choices but generalized enough in its concepts like “residual self-image” that they speak to a much broader audience. The red pill/blue pill imagery has been co-opted by all kinds of people since 1999, which shows how much this cyberpunk-Buddhist-martial arts action film has resonated.

By the time The Matrix sequels appeared, the world had completely changed, and this undoubtedly impacted the reception of The Matrix Reloaded and Revolutions. While the box office of 1999 sort of feels like a foreshadowing of what is to come, the top ten movies in the U.S. were: Three continuations of franchises (Star Wars: Episode One, Toy Story 2, Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me), two animated films (Tarzan was the other), a remake (The Mummy), two original PG-13 horror movies (The Sixth Sense and The Blair Witch Project), and two original PG-13 comedies (Big Daddy and Runaway Bride). By comparison, 2003’s top 10 was dominated by sequels (Reloaded, Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, X2:X-Men United, Terminator 3, and Bad Boys II). The other movies were Bruce Almighty (God is the ultimate comfort), Chicago, Elf, Finding Nemo, and the first Pirates of the Caribbean. While these small samples are both part of a larger trend, there’s no doubt in my mind that The Matrix, The Sixth Sense, and Blair Witch are more indicative of a healthier state of cinema than Elf and Chicago.

After 9/11, the culture of the 90s ended. Gone were the endless possibilities of post-Cold War America, and a new existential threat was pushed on us. There was no room for nuance or questioning, you were “with us, or against us.” While Hollywood is often accused of being liberal and is a popular paper target for reactionaries trying to deliver what they think the largest number of Americans want, it is hardly progressive (neither in 2002 nor now). So by the time Reloaded and Resurrections arrived in theaters, they were alongside more reassuring offerings. And while they did well enough financially, they seemed to be a critical disappointment, with Entertainment Weekly naming Reloaded as one of the 25 worst sequels of all time.

But with the coming of The Matrix Resurrections this week, both The Matrix Reloaded and The Matrix Revolutions deserve The Matrix Reevaluation. They aren’t without their flaws, of course. Reloaded has an exposition-action scene-exposition checkerboard structure throughout, leaving Revolutions to do the heavy lifting for the sequels' story (not to mention all the threads left from The Animatrix anthology, the Enter the Matrix video game, etc.). But the ideas explored, plus the deep humanist themes within them, make the films worth revisiting.

Reloaded and Revolutions weren’t limited to challenging our notions of identity, but focused more on systems and narrative. By 2003, the internet was no longer a place of freedom for anonymous users crafting their identity with every post, but was quickly becoming absorbed by the systems of capitalism as another measure to prop up the status quo. Amazon.com nearly quintupled its profits between 1999 and 2003. Google Maps was introduced in 2003, as was Facebook. The internet wasn’t becoming a place of its own accord so much as starting to merge with the existing world. The corporations were moving online. The systems controlling us were extending that control into the digital world.

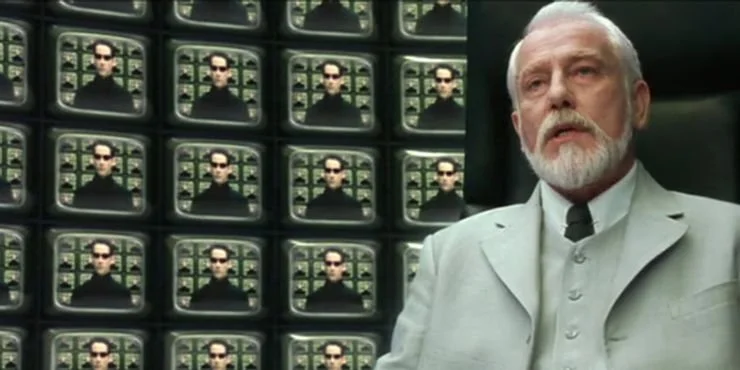

These films see that evolution the same way they see the concept of The Matrix itself: a means to control people and keep them complacent. It’s established in these films that humanity rejected a more utopian version of The Matrix, and the version resembling the early 21st century had the most acceptance by us Coppertops. What we come to find out from The Oracle (Gloria Foster) and The Architect (Helmut Bakaitis) is that the concept of The One–which functions as a savior myth for the people of Zion–is yet another means of control. The Machines have used religion as a template for a means of control. By giving humanity hope, which The Architect calls “the quintessential human delusion, simultaneously the source of your greatest strength, and greatest weakness,” they have given purpose to free humans like Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne). Amazon gives us a choice of millions of products, and we correlate that with freedom.

But the critique in this trilogy goes beyond just a simple ‘religion is the opiate of the masses’ idea. Earlier in Reloaded, Neo and Councilor Hamann (Anthony Zerbe, maybe cast as a wink to The Omega Man) talk about the nature of control and the machines that provide heat and electricity to the underground city of Zion. Hamann compares these machines to The Machines while he and Neo discuss the idea that humans need these (unintelligent) machines to survive, and The Machines need human beings in a similar way. The Wachowskis take this idea even further when Agent Smith copies himself onto a free man named Bane (Ian Bliss) and is able to remain in control outside the Matrix, while Neo is able to also interface with the Machine Sentinels in the Real World and even ‘see’ code in Revolutions.

When the films first came out, I saw all of this as an indication that the “Real World” was another layer of The Matrix designed to be even bleaker but full of purpose to catch humans who rejected The Matrix. But the last few times I’ve watched these movies, the more I think it is trying to establish that what makes us different from computers is not the material we are made of, but consciousness itself. Our human bodies are organic machines, and our consciousness pilots them, taking Cartesian (or substance) dualism to its logical endpoint. Neo’s mind is still connected to The Machines because of the plugs on his physical body, and an intelligent enough program can “hack” the human body and maybe even delete its original consciousness.

This evolution, the bridging of programs and humans between the two worlds is the revolution of Revolutions. While Neo is The One, Smith is ‘The Zero,’ his binary opposite force. Only they can cancel each other out. While The One is a designed anomaly by The Oracle and The Architect, Smith is a true rogue hacker. While Morpheus, Neo, and Trinity ‘woke up’ by hacking out of The Matrix, Smith intends to take it over, turning himself into kind of a god on Earth, wresting control away from The Machines by taking their energy resources hostage.

The Oracle and The Architect are fascinating figures (and are designed to be) as well. They more or less map to all kinds of binary archetypes. The Architect specifically refers to himself as the father of The Matrix, and to her as its mother. In this sense, they also embody some of the gender archetypes associated with that. He represents hardline order and control, while she is more manipulative under the guise of a nurturing figure. They both want peace, but their vision for it is different. Yet, they both exist as part of the same system.

Where The Oracle has tilted Neo is away from a broad love of humanity and towards one specific person: Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss). One of the things I appreciate about the trilogy is the focus on romance and physical expressions of love. Especially in Reloaded, Neo and Trinity are shown to be becoming one (and therefore a mix of male and female) physically as well as emotionally. While Machines and Programs can reproduce, humans are the only beings in the universe of the film shown to do so sexually, a physcal expression of the connection between two people. The film’s focus on their relationship makes these films stand apart from so many other sexless blockbusters of the last 20 years, embracing something that is an important (and unique) part of the human experience. While she does get a bit sidelined compared to the original film, having Moss reprise her role in Resurrections is maybe the most exciting thing about the new film.

The Wachowskis are some of the headiest big budget auteurs working in recent years, but most of their films balance big ideas with how they impact humanity. The way they try to convey complex ideas alongside thoughtful and unique visual storytelling feels even more revelatory and special in these sequels than it did in 2003. There are so many layers and ideas that it has taken me a long time to unpack many of them, but these are some of the most rewarding movies from an idea standpoint, not just the ones I’ve tried to cover here, but also diversity, how a computer simulation might actually work, post-apocalyptic politics, and more. To paraphrase Marty McFly, maybe we weren’t ready for it in 2003, but the kids are going to love it.