JOSIE AND THE PUSSYCATS at 20: DuJour still means masterpiece

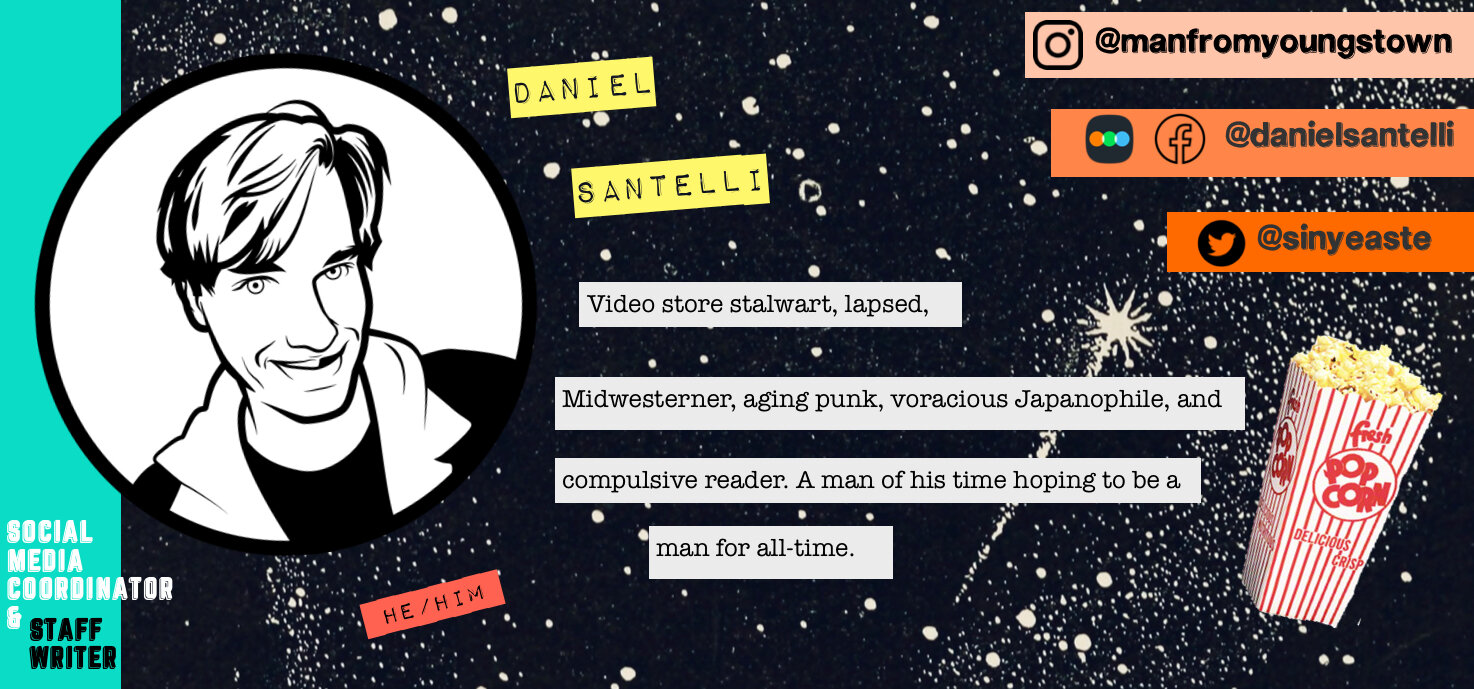

by Dan Santelli, Staff Writer

Cheerfully derisive and unnervingly prescient, Josie and the Pussycats fashions a spangled fusion of madcap Saturday-morning camp and creeping dystopian paranoia that draws smiles, guffaws, and even a bit of blood. Upending expectations from the word go, the film’s prologue propels us into a throng of screaming, manic youths on a tarmac who look on as voguish boy-band DuJour serenades them with their chart-topping hit about…well, anal sex. But the film’s first joke is more insidious: the roar of MGM’s Leo the Lion segues into the shriek of an adolescent girl, throwing us off balance and conflating the targets of the movie’s puckish satire–the purveying entertainment business and the consuming youths. A delirious omen of things to come, Josie and the Pussycats lets loose a cavalcade of anarchy, 90s girl power, and late-capitalist woes, a $30 million lampooning of its target audience and the industry that financed it.

Ostensibly a teen-comedy romp, loosely inspired by the Archie Comic, tracing the trio’s rise through the music ranks, the actual plot thrust concerns–of all things–corporate malfeasance, conspiracies, subliminal messaging, and consumerist excess. The product of wunderkinds gifted creative control after passing on the project (twice), Josie chases humor and glee with a stealth sci-fi premise that would leave Marx in tears and Trump taking notes. To boost the economy, the music industry and the (vaguely totalitarian) U.S. Government join forces to insert “advertising suggestions” into trendy tunes, thereby brainwashing teenage consumers into embracing conformity, propagating fads, and sinking so low as to get hooked on Zima. Ignorance is bliss for the performers, as they’re promptly iced after catching on. Pulling the strings are cunning Fiona and her snooty assistant Wyatt Frame, played by Parker Posey and Alan Cumming in performances so endearingly overripe you’d be hard-pressed not to cry “Oscar.”

And then there’s the Pussycats. Josie (Rachael Leigh Cook), Melody (Tara Reid), and Valerie (Rosario Dawson), embodying the spirit of pop-punk, nonconformity, 90s slackerdom, and female solidarity in one unit. Like most everyone in the film, they’re broadly drawn, cartoon personas characterized by commonplace attributes: Josie the headstrong leader, Val the cautious pragmatist, and Mel the cheerful space-cadet. It’s easy to see why this movie became a cornerstone for many young millennial women. Here, girl power transcends being simply a catchphrase and garners genuine emotional resonance via the sisterhood of the Pussycats; because Cook, Reid, and Dawson (all good on their own, great when they’re together) convince us of their dynamic and its sanctity, they beat the Spice Girls at their own game. Diegetically, Josie, Mel, and Val also represent a diminishing demographic, the last vestiges of individuality in an increasingly homogenous world that cares little for the outsider and approves only when it’s de rigueur. They’re among the lonely few yet to be suckered in by the skewed views and defaced frames.

The paucity of sharp pop-satires in 21st-century American movies renders the neglecting of Josie and the Pussycats a curious miscalculation. A kaleidoscopic burlesque of society undone by groupthink, corporate idiocy, and oppressive product placement, Josie simultaneously relishes and skewers pop-culture detritus, mocks its own existence as a product for mass consumption, and mounts a caricatured taxonomy of Y2K culture. In the world of Josie, cultural speed-up has reached peak velocity, overlords exhibit racist tendencies, and incite (female) rivalry to expunge the unwanted, the threat of losing your identity lurks in the shadows, and MTV hosts moonlight as assassins. The work of production designer Jasna Stefanovic (Cube, The Virgin Suicides) and cinematographer Matthew Libatique (Requiem for a Dream) serves as another relay for comment. Heightened realism punctuates the early Riverdale scenes, before the palette gives way to an array of progressively lurid pastels as the Pussycats attain fame. Stefanovic’s set design is brilliant: from the glossy, jet-black modernism of MegaRecords HQ, no doubt inspired by Ken Adam’s War Room in Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove, to the homes of entertainment insiders, decked out in kitschy art and gaudy hues, that impart the ostentatiousness of people with too much money and not enough taste.

Modern satire occasionally threatens to take itself too seriously, as if a lightness of touch would undermine effect. Stern nihilism can entice audiences with a seductive cool and the impression of “importance”, but it can also result in heavy-handed monotony that stunts the commentary. Kaplan and Elfont do one better; they dare to be silly, dare to be stupid: the Pussycats emerge from a makeover (shot in the style of late-career Tony Scott) looking practically the same; Josie merchandise overlays a music video; rising success coincides with ever more garish fashions; and a rioutous Rachael Leigh Cook/Parker Posey catfight features Twinkies as weapons and Advil decals glued to the floor. That dissonance is key to the film’s appeal, a tension that reframes our perception of the dystopian speculation and capitalist excess without sugaring the implications and what they signify–it morphs the film into a caustic nightmare-comedy. Kaplan and Elfont’s position is self-evident–there is no missing the point of this movie–and the raw materials are familiar, but, of course, a joke is distinguished by context and execution: their earnestness and zeal take them a long way. Saying “the dumber it seems, the smarter it gets” misreads the gambit. Josie occupies a peculiar, nebulous zone where the critique of social ills and the formal absurdity work in tandem, where campy hysteria is an extension of societal dysfunction, and where joke delivery tickles the funny bone while the associations break the skin. Not everything cuts deep, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

In essence, Josie and the Pussycats continues a cinematic dialogue that started as far back as Chaplin two-reelers and flowered in the 1950s, when filmmakers like Frank Tashlin (The Girl Can’t Help it) and Yasuzo Masumura (Giants & Toys) crafted their own exaggerated musings on capitalism run amok. A former WB animator, Tashlin’s live-action cartoons are Josie’s true stylistic precursor, but not even Tashlin’s dissonance between nightmarish inventory and spirited execution was as pronounced. The comparisons with 1997’s Spice World seem inevitable, but Josie plays more as response than successor; in the spirit of Godard’s belief that filmmaking functions as film criticism, Josie addresses the hypocrisy that undercuts Spice World by filtering the ribbing of prefab groups, hype, and itself through the remove of a fictional band. Stylistically, a better point of comparison from 1997 is Paul Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers.

“Satire is what closes on Saturday night,” exclaimed playwright George S. Kaufman. Grossing less than $5 million on its opening weekend in April 2001, exhibitors swiftly ushered Josie, Mel, and Val out of their multiplexes and tossed them away like soiled kitty litter. Critics rolled their eyes, audiences stayed away in droves, Universal tossed their baby out with the bathwater–an executive purportedly said of the film, “dead on arrival.” (Its biggest fans upon release were Bono and Angry Samoans-singer Metal Mike Saunders; the latter wrote a most favorable review of the film and its soundtrack in The Village Voice.) The financial failure thwarted sequel potential and left the creatives confined to that purgatorial domain known as Movie Jail. Rachael Leigh Cook’s career as a Hollywood lead ceased; Kaplan and Elfont haven’t directed a feature since. But somewhere along the way, the flop became a bop. Reevaluation first transpired online, then in print; Mondo reissued the bangers-all soundtrack (co-produced by Babyface and the late Adam Schlesinger) on a spiffy vinyl; entertainment journalist Russ Burlingame’s IndieGoGo-funded oral history is due out later this year–it’s appropriately titled Best Movie Ever: A Totally Jerkin’ Book.

Kaplan and Elfont’s second directed-feature, Josie and the Pussycats thrums with the carefree energy of a debut. Every idea they ever had seems to have gone into its making, yet it still holds the thread that binds: can the bond of friendship withstand the onslaught of fame? In Josie, their style, both visual and comic, harnesses a sugar-rush vigor so jovial and effortless you wish the laws of physics would get out of their way; it works the viewer into a state of perpetual giddiness, and the film is a masterclass in sustaining tone. Few studio films of the last twenty years work as hard as this in going beyond the parameters and expectations of genre to explore their potential. Joker takes the Clown Prince of Crime out of canon, but restricts him to the preordained destiny and tenor of another film artist’s making; Josie empowers the Pussycats to navigate their own path within the expanding diegesis while the film marches to the beat of its own drum, too in love with the idea of being itself to worry what others think. If watching filmmakers exploit imagination and push past the framework constitutes one of the great movie pleasures, then Josie and the Pussycats is pure cinema.