Spielberg Week: DUEL, Dads, and Demonic Trucks

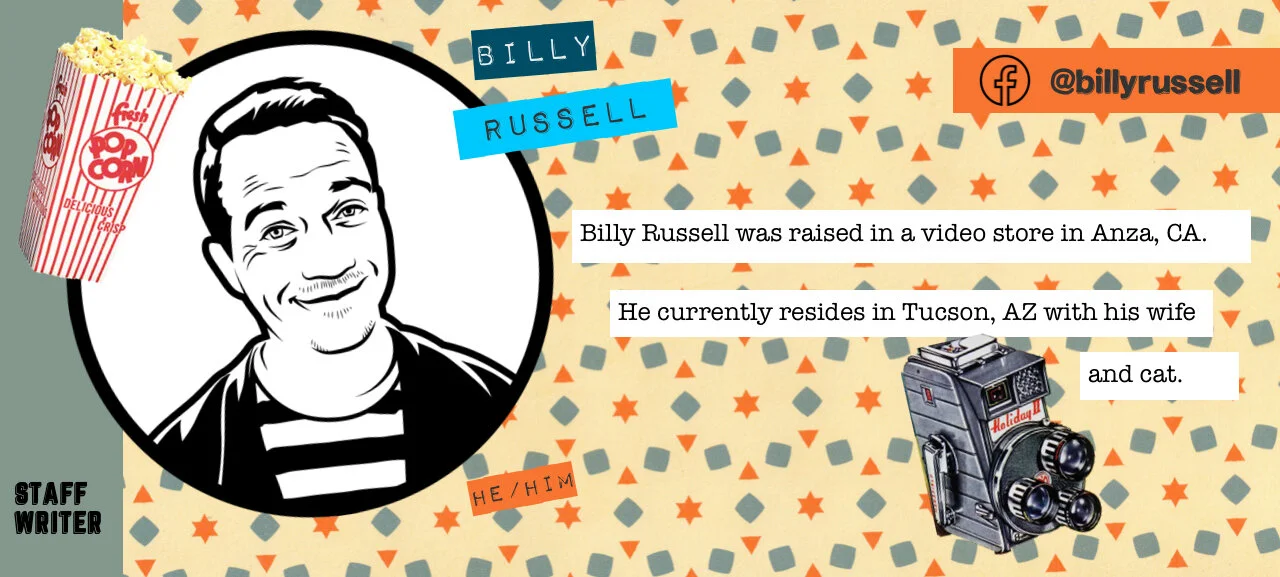

by Billy Russell, Staff Writer

My dad and I used to talk movies. I can’t remember exactly how the conversation got going, but we eventually started talking Spielberg. “What’s your favorite Spielberg?” “What’s yours?” That sort of thing. I was in high school at the time, probably about 15, so I probably said my favorite, at that time, was Saving Private Ryan. That or Raiders of the Lost Ark. I can’t remember where my tastes lied at the time.

But I remember what my dad said when I asked. He said, “Duel!”

“What the hell is Duel?” I asked.

“You never heard of Duel?!” He was shocked. “I thought you said you liked movies, boy.”

He started explaining to me that it was one of those “movie-of-the-week” TV movies from the 70s. As a kid, I’d always been a sucker for TV movies, ever since I saw Dark Night of the Scarecrow and it scared the hell out of me, so I was intrigued. Plus, it was straight up suspense/horror? Aside from Jaws, Spielberg only dabbled in horror in elements. He had made some scary scenes, but outside of Jaws I hadn’t really seen him do much with it, so I was definitely sold. I had to see this movie.

My dad told me when the movie aired, it was a hit. He missed the movie on its first night it aired, but the TV stations had so many calls, they wound up doing an encore presentation. And then several more. Then, eventually, some minor re-shoots were done to up its run time to feature length and it was given a theatrical release.

When my dad saw it, he swears he said, “This Spielberg kid… he’s gonna be a big deal.” I tend to believe my dad on this. When you see the early work of a master, it can be pretty obvious who has an innate understanding of the language of film. Hell, I remember seeing some rerun of the TV show “Columbo” and being like, “This episode seems particularly well-made, who the hell made this?” only to see Spielberg’s name on the directed-by credit. Spielberg proved himself early with TV, pushing the cinematic quality of his projects as far as he could.

Duel was shot in about twelve days on an incredibly tight schedule. Since it was a movie-of-the-week, it had to be churned out quickly. The writing, shooting and editing schedules didn’t leave much for second guessing, so everyone’s creative impulses were firing off on pure instict.

Richard Matheson wrote the script, based on his own short story, about a traveling salesman named David Mann (played by a panicky, nervous Dennis Weaver) being tormented by a giant semi truck. The film frames it such that Weaver isn’t being tormented by the driver of some giant semi truck. No, the villain of the film is the truck itself. We never even know if there is a driver. The most we ever see of this alleged driver is a pair of cowboy boots. The truck itself seems to be driven by a demonic presence, delighting in the torture of some poor motorist at total random. David is just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

And that’s what’s so scary about Duel. The motivationless torture feels so real. David passed this truck, and either the driver, or the demonic force driving the truck, decided, “Fuck that guy,” and went after him. First, having fun with little pranks. The truck would pass him, then slow down to a crawl and allow him to pass, then repeat the process. Then, the ante would slowly be upped–until it was clear that there was nowhere else to go, until he was dead.

There are some truly spectacular setpieces in Duel, with trucks crashing through phone booths, tension being raised over the threat of an entire school bus full of children being killed just to teach David a lesson, but my favorite is a quiet one. David stops at a truckstop to recover from a near-death encounter with the truck. In one long, unbroken shot, he goes to the bathroom, splashes water on his face, then returns to the dining area, only to see the truck that almost killed him now in the parking lot. Its windshield like eyes, staring at him. And he spends his meal wondering who, if any of these other truckers, it could be. And he has to decide if he has the courage to confront him or not. The tension mounts and mounts into almost unbearable levels, and the way it all pays off is such a subversion of what we’ve come to expect from these types of encounters in these types of movies.

Duel sets up a lot of Spielberg’s trademarks that he would use throughout his career, but since this was his first feature, it’s a lot more experimental than much of what he would do after he’d begun to refine his techniques and define himself as a director. I love the discordant music composed by Billy Goldenberg and the workmanlike editing of Frank Morriss. He would find longtime collaborators in John Williams and Michael Kahn, but Goldenberg and Morriss brought a certain energy to Duel you just can’t replicate. There was a rawness to it. An edigness. Some rough quality that felt alive. Duel is the closest thing to punk rock Spielberg ever made.