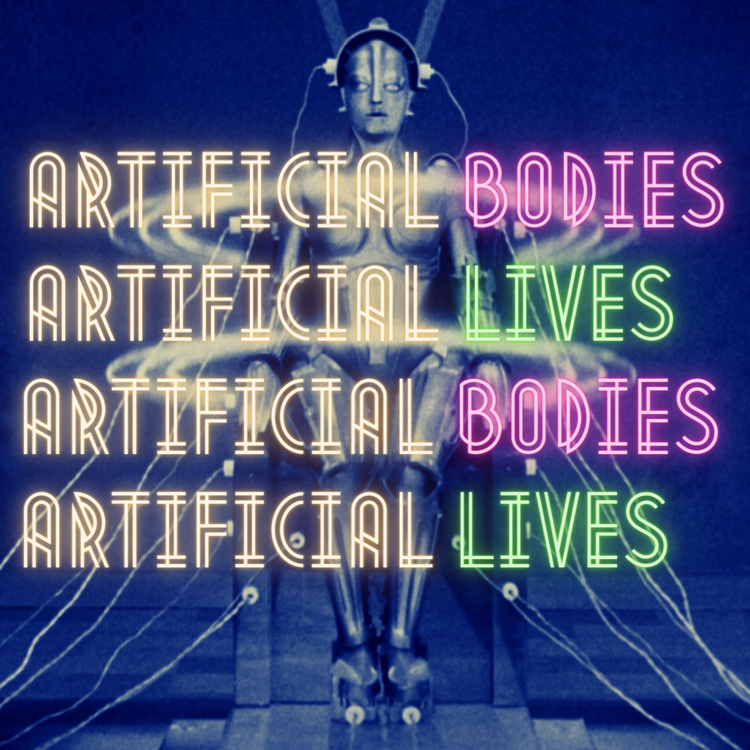

Artificial Bodies, Artificial Lives: METROPOLIS

by Tessa Swehla, Staff Writer

The impact that Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) has had on popular culture is difficult to calculate. Hitchcock, Kubrick, and Lucas all pay homage to it, as well as a surprising number of musicians from Queen to Madonna to Janelle Monáe. In many ways it is the quintessential German expressionist silent film, combining Bauhaus functionality with Futurist dynamism and Gothic atmosphere. With viscerally beautiful cinematography by the great Karl Freund and effects designer Eugen Schüfftan, it is a masterpiece of early effects and pioneering camera techniques. Metropolis–at its core–is a film that examines the symbiotic relationships between industrial technology and capitalism and introduces one of the most recognizable androids in cinema in the maschinenmensch or machine-person, the iconic metallic feminine automaton who would become the mold for generations of film androids to come.

Before I discuss the maschinenmensch, it is important to note the context in which she exists. Set in a distant and unknown future, the titular urban Metropolis is really two cities. The wealthy industrialists and executives live in gilded skyscrapers, while the workers live underground so as to be close to the machines that they must operate to keep the city functional. The workers themselves are dressed in dingy coveralls and covered in soot from their labors, while those who dwell above wear white and seem to have nothing better to do than to chase each other through beautiful gardens, which is where we meet the hero of the film, Freder (Gustav Fröhlich).

However, this dystopia doesn’t just rely on the workers to mind or repair the machines: the workers are sometimes literally part of the machinery they operate, blurring the boundaries between humans and technology. They pull levers in synchronized succession, turn dials with their bodies, and generally function as human cogs. In fact, their presence is so integral to the functioning of the Heart Machine–a name which signifies that the city itself might be considered an android of sorts–that they work in around-the-clock shifts of ten hours, shuffling back and forth to work in lockstep together, numb from exhaustion. When he witnesses an explosion that kills several workers, Freder, in one of many Biblical hallucinations he has throughout the film, imagines the workers as human sacrifices to be consumed by the machine.

Enter the maschinenmensch. When Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), the architect and chief industrialist of the city, discovers that the workers are organizing, he consults his former partner and romantic rival, the inventor Rotwang. Here is where the film takes a turn into the truly gothic. Rotwang reveals that he has created an android to resurrect his and Fredersen’s dead love Hel. He is not only a mad scientist; he is also a practitioner of the dark arts, symbolized by the giant pentagram scrawled on the wall behind the maschinenmensch in her introductory shot. He willing to sacrifice everything, including one of his hands (cyborg alert!) in order to resurrect his lost love in robot form.

Rotwang’s motivations may be to return Hel to him, but his descriptions of the purpose of the maschinenmensch and her subsequent arc in the film formed new tropes about androids, tropes rooted in gender stereotypes and anxieties. The first trope comes from the Greek myth of Pygmalion, a sculptor who falls in love with his own creation of the ideal woman. Rotwang may have loved Hel, but by recreating her as an android who cannot access Hel’s memories, personality, or agency, he is essentially creating a fantasy Hel who will be what he wants and choose him instead of his rival. He tells Joh that “she is the most perfect and obedient tool which mankind ever possessed.” Before Metropolis, robots and androids in film were mainly masculine or non-gendered in appearance. This film established the idea that androids could be sexual or even domestic fantasies played out often for the benefit of men, defamiliarizing the gendered ideals and performances that social norms insist on. There is even a specific term for this kind of robot in science fiction: gynoid or a robot that possesses a feminine appearance. In many ways, the maschinenmensch is the prototypical gynoid, the grandmother of Rachael, Ava, Lisa, and the Fembots.

At Joh’s request, Rotwang gives the maschinenmensch the appearance of Maria, an influential organizer for the workers and his son’s lover. They instruct her to cause chaos in the labor movement by inciting both sides to violence. Helm, who plays both characters, does some exceptional work here. She plays Maria as a chaste, saintly maternal figure and the mascinenmensch as a black-eyeliner wearing harlot whose sexual swagger and flirtatious winks can drive men to murder, despite her somewhat jerky movements. She agitates the workers underground in one moment and then strips, Salome-style, to a leering mob in tuxedos in the over-city the next. At one point, the male gaze–a term that I believe has been overused into meaninglessness but nevertheless is appropriate here–is literalized in the form of dozens of disembodied eyes of the men in the crowd, all fixed on the lurid fantasy that she embodies.

This brings us to the second trope that this film introduces into science fiction cinema: replacement anxiety. The maschinenmensch, according to Rotwang’s wishes, is intent on destroying the city by impersonating the real Maria. This anxiety of technology becoming so far advanced that it could begin to imitate and manipulate humanity represents not only a defamiliarized fear of the majority being replaced by a minority (more on that later) but also a deep-seated fear of women weaponizing the sexual fantasy created by men. The maschinenmensch may predate the femme fatale of noir films, but she is just as dangerous and calculating. In the end, she is burned as a witch for her part in the climatic catastrophe, which is really the only way her story could end. However, Lang’s maschinenmensch would outlive the film, becoming the first statement in a long conversation about gender, embodiment, and labor that persists in science fiction today.

Next month, I will discuss cyborgs and the technology of queerness in James Whale and Frankenstein films!

Note: There are many different prints of Metropolis available due to editing by theater owners over the years. I highly recommend watched the same print I did, The Complete Metropolis, which was restored in 2010 and has a runtime of 148 minutes.