Noir is the Colour of Asphalt: A Roadmap

Every year, when the darkness returns to our early evening, MovieJawn also returns to the dark for our annual celebration of Noirvember! Check out all of the previous articles here.

by Jo Rempel, Staff Writer

Ask someone to define film noir for you and you’re likely to get a smattering of tropes, which while discretely clear (“femme fatale,” “hard-boiled detective,” “unreliable narrator,” “past coming back to haunt you,” etc.) do not paint a complete or cohesive picture. Each is its own theoretical lens, a genre in its own right. So while Leave Her to Heaven (1945) is defined by the femme fatale, Out of the Past (1947) by its hard-boiled detective, and In a Lonely Place (1950) by spectres of the past, I’d like to propose a less human lens for the genre: cars and roadways.

So many classics have etched into my mind literal intersections with fate. What would Sunset Boulevard (1950) be without its desideratum of a driveway; In a Lonely Place and The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) without their roadside murders; Double Indemnity (1944) without its sputtering getaway car; or Fallen Angel (1945) and the aforementioned Postman without their stoic leads being able to drift from one highway town to the next?

The canon I’m drawing up today are of those essential noirs that keep it car-centric throughout. Each of these pictures builds its own perception of the motor, but before diving in, I’d like to draw a few conclusions regarding the broad strokes of noir. First, there is the aesthetic level. In his 1972 “Notes on Film Noir” for Film Comment, Paul Schrader distinguishes film noir as oblique and vertical in their design: “adher[ing] to the choreography of the city, and is in direct opposition to the horizontal American tradition of Griffith and Ford.” Shot from the driver’s POV, road markings extend vertically, pulsing out a heartbeat that’s both detached and unsteady.

Next, there is another more thematic riff on German expressionism. In America, the Weimar cinema’s Orientalist fascination with the encroaching Other, depicted obliquely in seminal works like The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1920) and Nosferatu (1922), had been translated into the allure of rapid urbanization at home. The city has been around long enough to have untold mysteries of its own. Like jazz and apartment complexes, the car, while innocuous, can serve as a synecdoche for urban blight.

For later entries on the list, there is also the influence of WWII-era newsreel footage, as well as neorealism to consider. These brought about a greater desire for contemporary and de-artificed “social problem” films among audiences and directors. If a director were to really show the streets’ character, they would have to move beyond the studio backlots. Of course, the issue of studio funding would go away. Richard Borde and Etienne Chaumeton hypothesize in A Panorama of America Film Noir, “that the Hollywood producers only accept a realist screenplay to the extent that it’s capable of being noirified.” So the car is able to provide necessary excitement, while those who spend their days behind the wheel see, and themselves exhibit, the day-to-day struggles of America.

“Car noir” hasn’t followed quite followed the road to becoming “neo” as other subgenres have. Taxi Driver (1976) and Collateral (2004) are the exceptions which prove the rule, filtering crime through men stuck in dead-end jobs. More in line with current trends is Ambulance (2022). That film burns rubber straight through the noir city, in line with the wanton destruction of Speed (1994) or The French Connection (1971).

The freeways are no longer spaces for contemplation. And so with history and its prospects in mind, the following picks are presented in chronological order:

They Drive By Night (dir. Raoul Walsh, 1940)

They Drive By Night actually precedes The Maltese Falcon (1941), often considered the start of American noir, by a year. Noir fixtures Humphrey Bogart and Ida Lupino both star, and the film is adapted from James Curtis’ novel by future screenwriter A. I. Bezzerides. The cast, crew, and plot beats are ultra-typical. Although the surreal, betrayal-laden atmosphere which propels noirs to greatness is lacking, the film connects all the dots while missing the shading.

George Raft and Bogart star as Joe and Paul Fabrini, freelance trucking brothers trying to make their way out of debt and finance their own company. Thematically, the film splits itself evenly between a social realist film and a psychoanalytic one. The first half is all struggle, with Joe and Paul dodging payments and trying to stay independent. George Rondolos (George Tobias), corporate boss, is both a friend and a source of temptation. They drive by night, as the title goes, unseen. Struggling against the road, the cars themselves, and your own body, struggling to stay awake. The road is destiny and you can’t fight it, so Paul ends up out of commision—all the more shocking given that it’s Bogie.

The second half sees Joe concede to Rondolos and move into upper management; now his danger is Lana (Lupino), the boss’s wife. Lana has been eyeing Joe for years and can’t take no for an answer. Thus begins a classic husband-murder plot. Rondolos remains affable, while Lana is a riot, brazen in her contempt for playing the part of wife.

The tense fraternal tale spirals into one of Hollywood’s worst odes to Protestant gumption, but Lupino’s star-making neurosis remains as a standout. Her Lady Macbeth-like fixation is over her own murder weapon: the laser-activated, and thus fingerprint-free garage door with which she seals her sleeping husband in with the idling engine. By now industrial machinery can work overnight without the need for human hands. Bezzerides was working at a camera factory before Warner Brothers scooped him up, and there’s a fear of the long haul on display here that reaches to both the road and the conveyor belt.

Detour (dir. Edgar G. Ulmer, 1945)

Al Roberts, Detour’s narrator, starts out trying to thumb his way from California to New York. Sitting down at a roadside diner, we’re graced with one of the most despondent close-ups of all time: natural lighting shifts to pitch black save for a circle targeting Al’s eyes, invoking a car’s headlights. A patron’s jukebox pick recalls his recent past, hitch-hiking from New York to LA to visit his girlfriend, Sue (Claudia Drake). He may be in control of the narrative, but he certainly isn’t ever behind the wheel.

Literal distance is symbolic, too. Al is a sad sack even when he and Sue are together. He’s a talented bar pianist discontented with his station in life. Every encouraging word from Sue is met with a zinger about arthritis or making his Carnegie debut in the janitor’s closet. Besides the obvious, this sense of perpetual failure connects Detour with the trucker films on this list. To be stable is to die, no matter what self-destruction the fast life entails.

Al gets his one lucky break in the passenger seat of one Charles Haskell, gambling addict with generational wealth and a lifestyle steeped in urban legend. Marks on his hand lead to the story of a femme fatale who’s more femme animale. “Three puffy red lines about a quarter of an inch apart,” Al’s voiceover observes. The road is infecting his mind by now, showing up in everything he sees.

Haskell’s sudden death by accident and chronic illness leads to a potentially bad story on Al’s hands, and so he takes a leap to avoid suspicion: become Charles Haskell and pawn “his” car once he gets to LA. Al cares so much about how guilty he looks that he becomes something else—truly guilty and another myth, drifting through an American purgatory.

Thieves’ Highway (dir. Jules Dassin, 1949)

Jules Dassin directs, this film being his last Old Hollywood feature. He had spent years in danger of being blacklisted already and would end up furloughed to England by Daryl F. Zanuck to direct Night and the City (1950) shortly after production. Thieves’ Highway is one of the most unrelentingly cruel pictures of its era: who knows what more time in America would have done to Dassin’s style.

Nic Garcos (Richard Conte) returns home from war to find that his father (Morris Carnovsky), once a truck driver, has lost his legs in an “accident.” Well, there’s no such thing as accidents here; every human suffering traces back to supply and demand. Nic understands that cutthroat wholesaler Mike Figlia (Lee J Cobb in a classic “heavy” role) is the cause of this market force. Pops doesn’t want Nic to join the family business, but revenge must be taken. Here, enterprise is nothing more than a cycle of dehumanizing violence. Nic’s quest is constantly undercut by Figlia, which only strengthens his resolve and lets him dehumanize himself in desperation for his cut.

Beyond politics, the film relates to trucks on an aesthetic level as towering figures of doom. Cinemascope, the death knell of noir’s studio style, would become Hollywood vogue: here, the 4:3 frame is warped to mammoth verticality. We look from the wheel up to the summits of California’s hills.

Thieves’ Highway highlights another use of cars, as Nic tries to sell his truckful of apples: migration, from Nic’s hometown to the urban market. The nightlife of the city is a source of both revulsion and redemption. He meets Rica (Valentina Cortese), a sex worker by the strongest code-era implication, and together they approximate domestic life. But Nic has stepped into a conveyor belt world, where nothing is stable like he wants, and he does not have the power to change things.

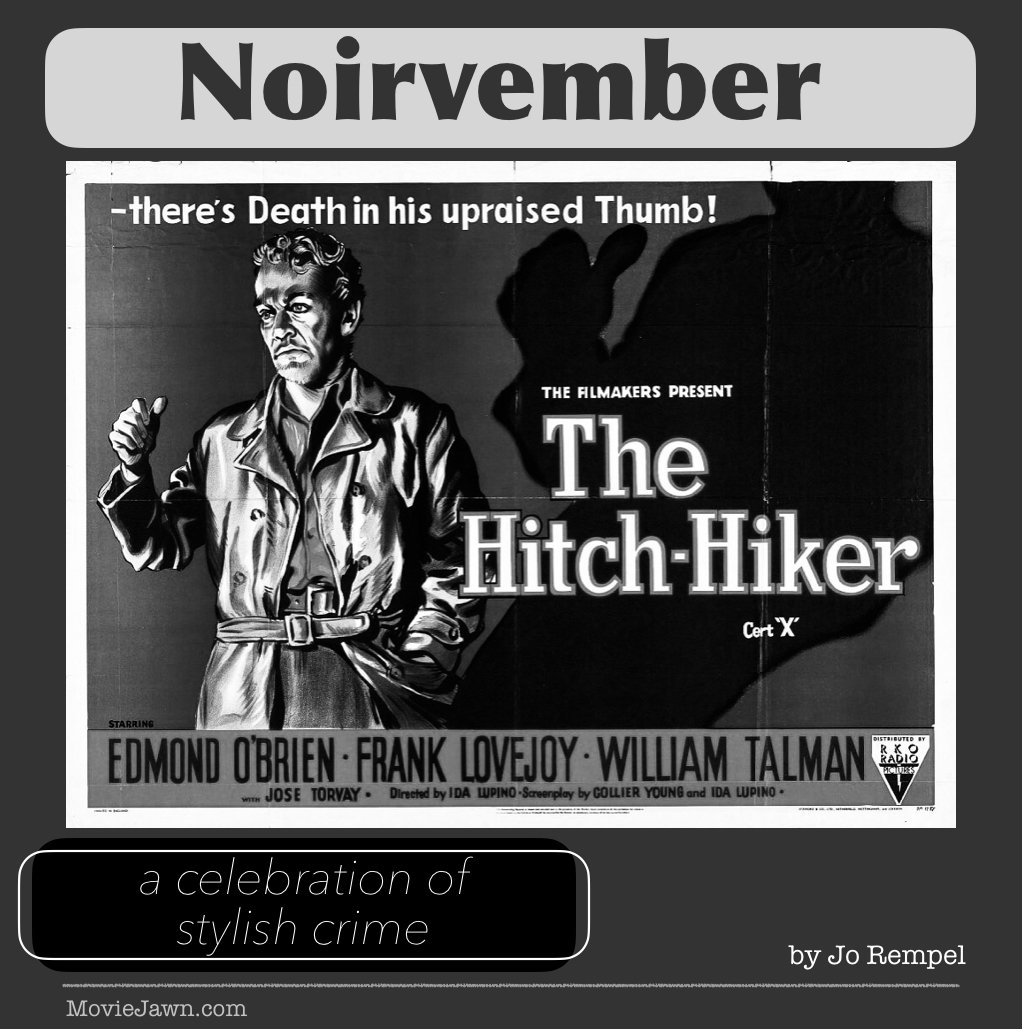

The Hitch-Hiker (dir. Ida Lupino, 1953)

Often touted as the only woman-directed classic noir, Lupino’s ripped-from-the-headlines thriller also happens to be one of the best. It was produced in collaboration between Lupino’s fledgling Filmmakers, Inc. and RKO pictures. California’s landscape is shot in harsh contrast by house cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca.

Best friends Roy (Edmond O’Brien) and Gil (Frank Lovejoy) are family men out together on a fishing trip, though at a fork in the road they decide on paying a visit to Mexicali instead. Whatever debauchery they might get up to there is implied in taking a literal “wrong turn.” The pair pick up a hitch-hiker while cruising through the night. Gun in hand, he emerges from the blackened back seat to declare, “Sure, I’m Emmett Myers.” From then on, they are held hostage by the notorious serial murderer played with biting cynicism by William Talman. Myers makes his own rules; he subjugates Roy and Gil to cat-and-mouse exercises just to test their strength.

Though he looks like he’s been haunting the road for decades, the character was based on Billy Cook, a former ward of the state who at 22 vowed to “live by the gun” and would be executed two only years later. Lupino’s domestic melodramas showcased the psychological pain of going your own way: The Hitch-Hiker is both a treatise to male friendship and political unity. While Myers doesn’t want Gil speaking “Mex” to the locals, we see American and Mexican law enforcement coordinate their efforts to stop him. The visuals, while expressionistic, handle these moral aspects as matter-of-fact. The first thing we understand is absence—loneliness, but also lack of physical borders between the landscapes of two supposedly different countries. For all its paranoid tendencies, The Hitch-Hiker does not despise the open road. It finds true strength in the sum of the overlooked people whom the highway ties into the maze of human existence.

The Wages of Fear (dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot, 1953)

So far I have been drawing a solid throughline for noir as a period/genre/urge relating to the urban United States. The Wages of Fear veers from this image: it takes place in a South American village where expats who once looked to strike their fortunes now dream of affording their return tickets.

When the film starts, we’re already embedded with Mario (Yves Montand) in Las Piedras. We’re in Uruguay, though that’s not made specific. Mario makes himself out as an outsider amongst the natives. His contempt, however, is a simmering kind: what’s truly explosive is an inferno raging in the oil fields 500 kilometers away, economic imperialism as seen from the bottom up.

The only way to quell the disaster is with nitroglycerine, transported from the village. It’s a suicide mission, taken up by four outsourced and senseless drivers—Mario, Jo (Charles Vanel), Luigi (Folco Lulli), and Bimba (Peter van Eyck)—split between two trucks.

Like with The Hitch-Hiker, much attention is paid to the environment. The trucks are a fundamental force of antagonism and decay, the camera lingering on the rubble knocked about in their wake. The drivers must adapt to their environment, which really means adapting to poor infrastructure. The first high-tension sequence is over a stretch of “washboard” road. At one point, near the end of the road, we witness a cleared forest and a lake of gasoline: the deep black is photographed so clearly that the screen seems to exhibit its same purple-green shimmer.

Henri-George Clouzot is often referred to as the French Hitchcock: certainly, he is a master of suspense. There are scenes in The Wages of Fear that are heart-pounding, slow, relying on the weight of the trucks. The silence of the jungle contrasts with the noise of the town. William Friedkin’s Sorcerer adapted the same novel as Clouzot and is its own beast, edging towards folk horror. There, the road seems to fight back; here it absorbs all our anger, greed, and yes, fear.