James Baldwin Abroad offers an intimate portrait of brilliance

James Baldwin Abroad - A Program of 3 Films

Directed by Sedat Pakay, Terence Dixon, Horace Ové

Runtime: 84 minutes

Shown at Film Forum and Brooklyn Museum of Arts

by Imani Sebri, Contributor

It is rewarding to watch yourself on screen. When I trekked to Film Forum to watch Baldwin Abroad, I took it as a chance to grasp this mammoth of a man I’d approached as a mythological figure. But I ended up watching sequences of Baldwin’s life that intersected so fluidly with mine.

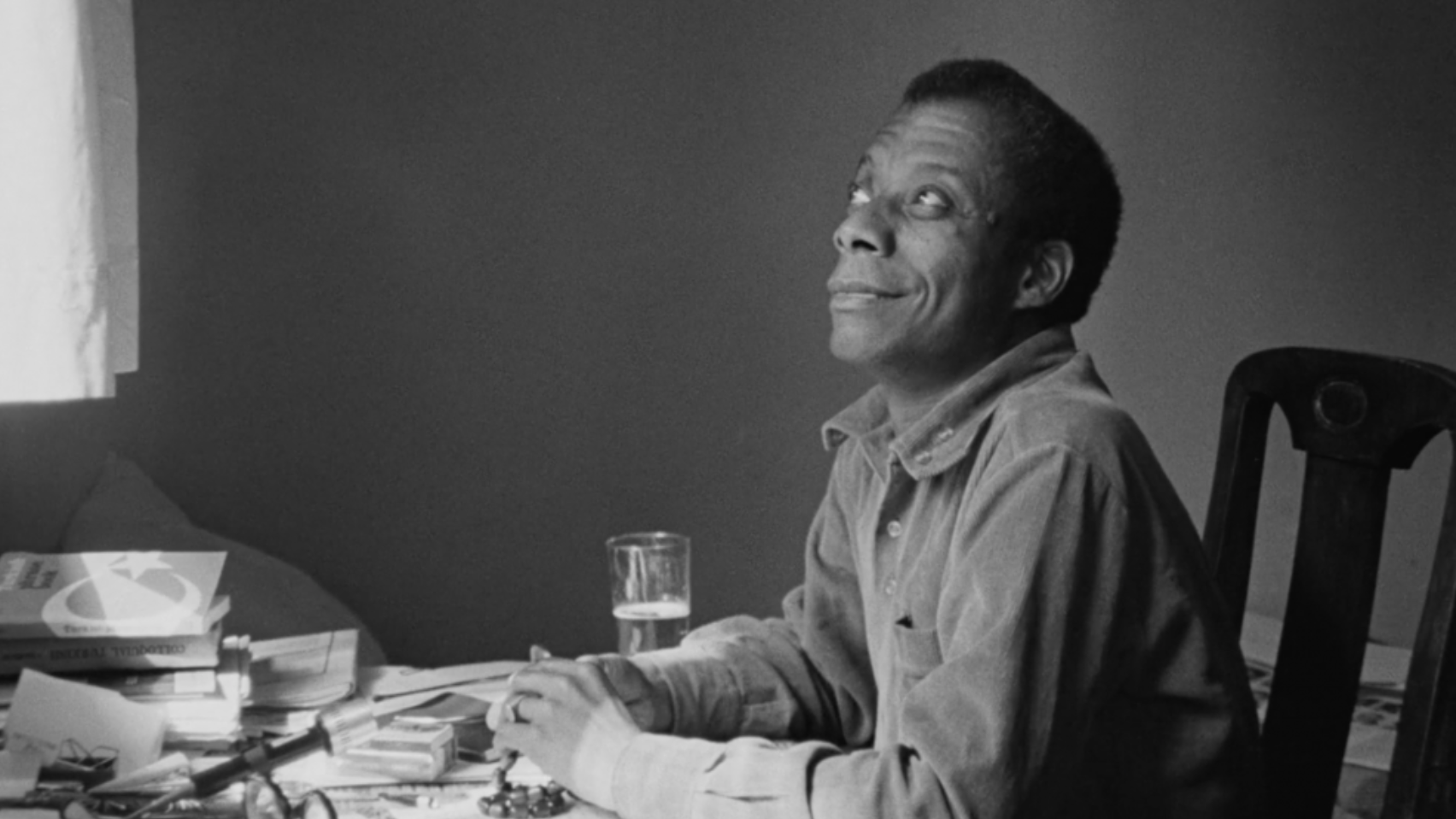

We follow James Baldwin in Istanbul, Paris, and London in James Baldwin Abroad.

The first film, James Baldwin: From Another Place (1973) runs 12 minutes. Filmed by longtime friend and playwright Sedat Pakay, I saw more of Baldwin’s interior than before. The opening scene is of Baldwin, candid and comfortable, in his bed. His voice overlays scenes of 1970s Istanbul – from the snippets of Baldwin on the Bosphorus Sea overlooking Topkapı Palace to him feeding pigeons on the Mosque steps. Baldwin ruminates about what it means to exist outside the United States and whether one is ever truly free of its hegemony.

I found myself in Istanbul, and years later, asking the same question — Who was I when I wasn't in America, and did it matter? When the hegemony of my country wasn’t on my back, was I free to be someone of my own making? It’s a question that’s stuck with me and one Baldwin comes back to time and time again.

It never occurred to me that I had traced Baldwin’s footsteps, at least geographically speaking. I’ve walked the windy side roads of Istanbul, trod the same waters on the Bosphorus, walked by the local mosques, big and small, and thought about the space I held here.

Sitting at his desk, stacked high with books, loose papers, and glasses, he candidly talks about the Black experience in America and the persistent interest in his private life, alluding to his being gay. He discusses how love has come to him in different forms, how it finds us all eventually and in ways we never expect. Here he offers an intimate and concise picture of the love ethic he believed in and lived by. Being able to watch Baldwin’s life lovingly captured through the eyes of his friend felt intimate and honest, a gentle introduction to a man I always felt just out of my grasp.

The second film, Meeting The Man: James Baldwin in Paris (1971), directed by Terence Dixon, opens with him walking along the Seine. The same river and landscape greeted me not six months ago when I visited Paris for the first time. The city where he lived nine years and where “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “Giovanni’s Room” came to be, looked back at me. He traversed the streets and sat with Algerians in Paris who, as Baldwin said, embodied the Black man in France. He even became a confidant and counselor to a group of Black American students studying in the city.

The 26-minute film is a back-and-forth between Baldwin and Dixon. Contentious at times, it’s a microcosm of race relations in the late 60s and early 70s. A sense of frustration is felt through the screen as Baldwin explains who he is and his work. He understands how intricately twined the personal and political are. Dixon didn't, and he tried to fit Baldwin's being into the infinitely limiting box of "writer"; a depoliticized, one-dimensional rendering of his character.

Baldwin says plainly: “I’m one of the very few dark people in the world who have a voice. That means something which no white writer can mean at this point in the world’s history. And I can’t really escape that. I don’t think I should even try.” We see so clearly how Baldwin occupies a particular cultural space in this moment. He cannot divorce himself from his blackness or his politics, and instead, uses his visibility to lean into the role he's been ushered into – whether he chose it for himself or not.

They stop in front of the Bastille, a fortress that doubled as a prison but was liberated after the French Revolution. Baldwin explains: “They tore down this prison…I am trying to tear down a prison too.” He understands that his words, fictional or not, can be a catalyst for change. Oppression seems inescapable, but Baldwin understands that words can topple empires. He uses his work to implicate the American public in the plight of Black life. It’s astounding how in-vogue Baldwin is. His understanding of art as a means of resistance rings true today.

Parts of Baldwin and Dixon’s interaction reads as an attempt to decode the Black American experience for white audiences. A mundane and draining violence that has been replicated time and time again by well-meaning white intellectuals and liberals. Baldwin stands in for the American Negro, stripped of history, given an identity, and subsequently picked apart for the sake of white education.

The transition to Beauford Delaney’s studio was a welcome one. Adorned with colorful paintings tinged with aspects of Van Gogh and expressionism. A young woman spoke about what Baldwin meant to Black people and he said, “in some sense, I did this for you.” A simple but significant sentence that reminds me: I am who I am today because Baldwin was there first. The innate sense of curiosity for stories that have followed me from childhood, I found in Baldwin. The need to be a witness, to document, to make people know what they would instead turn a blind eye to is in me because it was in Baldwin. I am not him in talent, discipline, or wisdom, but I still recognize myself in him, in his words.

It was also a striking portrait of white filmmaking at its worst. Ill-prepared and presumptuous, Dixon tries to create an “exotic survivor” in Baldwin, which Baldwin promptly rejects. At times, their interactions were difficult to watch, the tension palpable, but what Meeting The Man offered was a crucial portrait of a man whose unrivaled intellect and grace remained intact regardless of what the world did or didn’t offer him.

We conclude in 1968 London, with Horace Ové as the finale. Baldwin’s N****r captures an incisive public debate about Black identity, experience, and politics in Britain, America, and the Caribbean. It’s here Baldwin emphasizes the importance of relearning history through a critical lens, a conversation recognizable to contemporary audiences. His presence is complimented by Dick Gregory, an activist, comedian, and close friend. Their interactions are a delight to watch. The quick-witted banter between the two is on full display throughout, bringing a lightness to the bleak reality of civil rights activism at the time.

Ové captures Baldwin in his element, among people who are insatiably curious about what a liberated future could mean for them. He spoke tenderly about the power and love in a shared history, language, and struggle. Over generations and oceans, Baldwin and I remained in step with one another.

The curation of James Baldwin Abroad was touching. It shows him in his many forms: the writer, the activist, the mentor, the friend, the lover. I had always seen Baldwin as a brilliant writer and activist, which is not untrue, though I had overlooked the moments of joy, laughter, and tenderness that permeated his life and were woven seamlessly through his work. These documentaries captured that in its fullness.

The films are also a testament to our time. Baldwin describes himself as a “black man in the middle of this century” and that is what’s reflected in his writing. That statement is just as true now as it was in 1971 Paris. As Baldwin contemplates Black liberation, love and sexuality, and creativity as a means for survival, I realize how provocative and undeniable his mind was. Though it’s damning to have Baldwin hold up a mirror and demand we interrogate our complacency in the ills that shape our world today, it’s necessary. For me, it was an invitation to examine my role in disrupting the global status quo. It was an invitation to consider my life abroad as a means of survival. Finally, it was an invitation to be a witness and to document the world through my eyes, all as Baldwin had done.

James Baldwin continues to be a salvation for people who have felt unheard and unseen. This curation brought his presence to the screen authentically, and we experienced him as he wished to be understood, not disfigured to fit within the confines of the white gaze.

James Baldwin Abroad is a compelling, varied, but still intimate portrait of brilliance, one that moves and challenges the viewer to be a witness, just as Baldwin was, with grace, a sharp tongue, and wit.