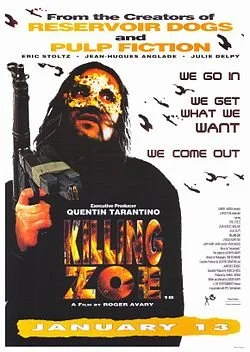

The Impossible Royale with Cheese #3: KILLING ZOE

Killing Zoe (1993)

written and directed by Roger Avary

starring Eric Stoltz, Jean-Hughes Anglade and Julie Delpy

by Alex Rudolph, Staff Writer

You know who really wanted to be Quentin Tarantino? Quentin Tarantino. During production on Pulp Fiction, well after the script had been finalized, Tarantino's collaborator and former video store co-worker Roger Avary got a call from Tarantino's attorney saying he'd either have to forfeit his co-writing credit and accept a shared "Story by" one or the chunk of the plot that Avary had come up with, the film's middle section with Bruce Willis, would be excised completely and replaced with something new. He could get diminished credit for his work or the work would be thrown away.

This happens a lot. People like to be seen as a project's sole creative force, especially when working in media like film and television, where there are dozens of people collaborating. Maybe Miramax was trying to cultivate an auteur whose name would be easier to market alone than with an occasional co-writer or maybe Tarantino was already trying to build up his cult of personality. Whatever the reason, he got sole credit as Pulp Fiction's writer-director, the genius behind everything. When something pops off, everybody wants to be the reason why. Tim Burton's name is all over The Nightmare Before Christmas, but Henry Selick directed it, Caroline Thompson wrote its screenplay and Danny Elfman wrote all of its songs. Burton, who had the basic idea and sketched designs for the film's characters, is the one who talks at Disney's press conferences. It's easier to think about movies like novels than it is to acknowledge who actually did what. "Written and Directed by Quentin Tarantino" is a lot more impressive without the "except for the third of the film co-written by Roger Avary" asterisk. Tarantino Zuckerberg'd a few friends on the way to becoming so identifiable.

For years, Avary was publicly hurt by getting minimized in the creation of Pulp Fiction, openly discussing the slight in Peter Biskind's Sundance/Miramax book history Down and Dirty Pictures in 2004. Ten years later, Avary, presumably while holding a sign that said "Please don't ask me about this or I'll break my NDA," told Vanity Fair he didn't remember that happening. Today, the two men host a podcast about movies they loved in their video store days. Before the falling out, Avary was poised to become as big as his friend. Who knows how much of this is real, but Killing Zoe supposedly only exists because Tarantino and his one-time producer Lawrence Bender found an excellent bank while scouting locations for Reservoir Dogs. After hearing about the location, Avary lied to Bender, saying he had written a bank heist script that would fit it perfectly. With Bender's interest piqued, Avary banged out Killing Zoe's first draft.

It's a ridiculous story, something that would only happen in a movie, but it really is a great bank. It's spacious without looking like an office building, generic enough that you could film in Los Angeles and pretend it was almost anywhere in the world. If a movie producer was ever to praise a bank to his friends, it would have to be like this one: decent-enough looking, with enough space that filming on location wouldn't be a pain.

Avary and Tarantino's relationship makes Killing Zoe's debt to the latter hard to define. Avary had written all of the Steven Wright radio dialogue in Reservoir Dogs and had come up with significant parts of Pulp Fiction. You can't dismiss him as a Tarantino copycat if he was there from the start, working on the material other writers would rip off. More importantly, he co-wrote The Open Road with his friend before Tarantino reworked the script into True Romance. And that's what Killing Zoe takes from, more than anything.

Zoe had its festival premiere in October 1993, one month after True Romance was released, and Avary either recycled a ton of the Open Road material that made it into True Romance or he copied off his friend's test and took liberal inspiration from the version of True Romance that Tarantino gave to Tony Scott. He either wrote fan fiction or he deserves more credit for coming up with the early Tarantino style. Because both True Romance and Zoe are about guys who meet sex workers in scene two, have deep, soul-bonding sex with them and then wind up in over-the-top shootouts as the movies end, with the guy wounded and the woman calmly walking him out of the bloody chaos. Zoe's got the requisite framed movie posters on apartment walls and conversations about movies and music. It's True Romance with a tighter focus.

That focus ends up being Killing Zoe's biggest strength, if you can make it through the parts where the focus makes you want to turn the movie off. There are, essentially, five long scenes over its 96 minutes. Where Tarantino made nonlinear storytelling one of his early signatures (as with Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, True Romance's script originally played with time), Avary's story might as well be in real-time. One thing leads to the next leads to the next:

1. Eric Stoltz, looking exactly like Travolta in Pulp Fiction, with this hair, earrings and suit, gets off a plane from the United States to France and a cab driver offers him access to escorts. I had assumed the music during this ride between the airport and a Parisian hotel was a bizarre remix of Moby's "Go" with slap bass and off-key yodeling, but it's actually part of the original score by tomandandy. It's so fun to look at Stoltz and then Travolta and think about Avary and Tarantino, two dorks, having the same idea of what a cool guy looks like. "Of course he would have greasy, shoulder-length hair," one would say, and the other would nod furiously.

2. Julie Delpy, the Zoe from the movie's title, meets Eric Stoltz in his hotel, where they talk and have a long sex montage not unlike the one in The Room (they even hit at about the same point in each film's running time).

3. Stoltz, who I have put off mentioning is named Zed, meets up with his French friend, Eric. They go back to Eric's apartment, meet a crew of thieves and briefly look at a bank's blueprints. Zed is a safecracker. Rather than plan the heist they're going to pull in that bank, they all smoke heroin. The subsequent 25 minutes of the film are shot partially out of focus.

4. Zed and his new crew go to an underground Dixieland jazz club.

That's the first half of the film-- four scenes over forty-five minutes, and the cameraperson has their hand skittering around with the focus for twenty-five of those minutes. It's not dissimilar to what Gaspar Noé might do, though he'd probably be punishing the audience. I think Avary's just making a stylistic decision that happens to make everything harder to watch. I can get annoyed when movies try to prove obvious points and think they're blowing your mind with arguments you couldn't disagree with, and that's what seems to be happening here-- Roger Avary felt he had to impress "heroin is bad and will make you feel bad" on the viewer and he did it by making twenty-six percent of his first movie into a headache. It's bold, at least.

At the forty-six minute mark, the crew don sequined masks and enter the bank. The fifth and final scene opens with Zed waking up in the back of a getaway van, hungover and maybe a little high, seconds away from a heist.

I love how many people there are here. Seven men jump out of the van and enter the bank, and it immediately feels like too many people. The job feels sloppy, the opposite of a story like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, where a handful of people move in tight orchestration. It's not like each of these men has a specialty, either. This is a bunch of guys with guns showing up and hoping things work out. They run into the bank yelling like children playing a game. As they get deeper into the building, they whip chains around, fire guns behind their backs and play air guitar on shotguns. Within minutes, the job goes wrong and they're bickering and pushing each other around. Back at the friend's apartment, the movie made a quick joke about how little time had been put into preparation and then a scene-and-a-half later, that joke becomes the first fuck-up in a long series of them.

The only problem with introducing so many characters into such a tight story is the limited time Avary spends identifying them. Each man, outside Zed and Eric, is interchangeable, his mask more idiosyncratic than his personality. You could get rid of the blurry heroin footage and have time to give a few of them names, at least.

As the crew are still happily fooling around, the movie gives us a quick flash of Zoe's face. She works at the bank and she's trapped in it with everybody else.

Zed's job is to open the big vault. Everybody else smokes cigarettes and dicks around in the bank's lobby, telling sex stories that don't really go anywhere. Eric shoots heroin in a bathroom stall. There's some interesting color work in the film. Eric's apartment is painted a solid blue and the bank's vault is a solid red. The lobby has bits of red and gets more overwhelmed by the color the closer we get to the vault. As symbolism, it's obvious. As an element of design, it's striking, helping all of these flamboyant characters in gray and navy suits really pop.

The heist includes one of my favorite tropes: a hostage who happens to be carrying a gun tries to have a heroic moment and unloads on his captors (the off-duty cop in Point Break is probably my favorite version of this character). In most movies, this doesn't pan out for the hostage, but he makes things a little more complicated before he's blown away. Killing Zoe's version of the character manages to kill one of the robbers and maims another. The crew start ripping their masks off. And then a phone rings-- the line, which they thought had been cut, is still active. An alarm has gone off. Police surround the bank. The crew start killing hostages to let off some steam.

As the movie progresses, they start killing each other. It isn't clear why, but that chaos is part of the tone. You don't really need to know their reasons beyond frustration, fear and hopelessness. In that way, the second half of the film mirrors the first half, with clear focus getting interrupted by hallucinatory nonsense. Toward the end, the members of the crew aren't even framed in the same shots. One of them will fire and then we'll cut to a different one falling down dead. You could have shuffled the shots around and achieved the same effect. All you really know and need to know is that everybody dies in the confusion.

Zoe and Zed reconnect and, in True Romance fashion, Zoe carries a maimed Zed out of the firefight as police rush in and kill everybody who hasn't already been taken out. They're okay. The movie ends in another cab. Zoe is not killed, despite what the title leads you to believe. Avary has said that "zoe" means life in Greek (a language nobody in the film speaks or references) and that the title means "killing life." All killing is killing life. You can't kill a thing that isn't alive. It's the bad title double-whammy of meaninglessness and pretension. Any other title would have served the film better, but that's Killing Zoe-- the artier, more abstract moments are always there to get in the way of what could be a fun, straightforward crime flick.

I do love that structure, though. Partly, I love long scenes. Mostly, I love claustrophobia. Reservoir Dogs primarily takes place in a single warehouse, but it uses flashbacks to break out. The world expanded, the audience got relief and you never felt locked down alongside Tim Roth. Zoe follows Eric Stoltz's Zed so closely that you're there with him, without so much as an exterior establishing shot to acknowledge the world outside the bank. It's nowhere near as successful as Rififi's thirty-minute-long heist, but it's trying, and that's worth something. Most copycats don't even bother trying, which, perhaps, lends credence to the idea that this is something more than one man stealing from another.

The year is 1993: There really isn't much tying Zoe to its time, though I guess 1993 is the only year you'd see Julie Delpy play a role this small in a low budget thriller. Her Three Colors movie was released in 1994 and Before Sunrise, which somehow cost twice as much as Killing Zoe to make, hit the year after that.

Tarantino defectors: None! This is our first and last example of the opposite-- Eric Stoltz appeared here one year before playing Lance the drug dealer in Pulp Fiction.

Weirdest member of the ensemble: He barely counts, but former porn star/current sex pest Ron Jeremy plays a bank teller for all of five seconds before he's blown away with a shotgun. He's the first casualty and he looks a little like Stoltz in full Mask make-up.

Weirdest pop culture reference: Characters talk about The Prisoner and a Dressed to Kill poster shows up, both of which make some sense, but the big sex scene is inter-cut with pieces of Nosferatu. I suppose it's more subtle than two characters dissecting the film in conversation, but it's a thousand times more awkward.

Most Tarantino moment: It's the entire skeleton of the plot, taken from True Romance.

Needledrop setpiece: There aren't any, which is surprising. All of the music comes from the composing team tomandandy, who would go on to work with artists like U2 and David Byrne while maintaining a prolific career writing music for films.

Innovations in the subgenre: Though the movie was shot in Los Angeles, it takes place in Paris, marking the first fake Tarantino movie set outside the United States (or Los Angeles, for that matter). Considering how much Tarantino stole from Jean-Luc Godard, this is a bit of a mirrors-facing-mirrors situation.

Most ridiculous line of dialogue: "In Paris, it's good to smell like you've been fucking to make them respect you."

Does it work? Mostly, and when it works it's well done.

Where did the writer/director go? Roger Avary is a weird case. He had his falling out and recent reconciliation with his buddy Quentin and he won an Oscar for his work on Pulp Fiction. He wrote and directed The Rules of Attraction, a movie overflowing with showy stylishness that is, like every adaptation of a Bret Easton Ellis book, significantly better than its source material. He wrote the Silent Hill adaptation that I think is pretty great and co-wrote (with Neil Gaiman!) the Beowulf adaptation that couldn't be less interesting. He killed a friend in a drunk driving accident and made Lucky Day, a pseudo-sequel to Killing Zoe, in 2019. In many ways, it seems like Avary should have had a parallel career to Tarantino's. I don't really understand how he managed to squander the momentum of the Pulp Fiction Oscar and his association with the hottest director of the 90s. I assume he's done uncredited script doctor work that I'll never know about, but that doesn't account for how few of his own films he's secured funding for. Is it bad luck? Do Hollywood's power players like The Rules of Attraction less than I do? You'd think he would have been able to make a Killing Zoe every few years. Before he killed a guy, at least. It could be that Avary just drifted away from Tarantino at the exact worst moment to do so. Zoe counted Tarantino and Bender among its producers, but neither man lent his name to an Avary project after that. Maybe Avary could have benefited from his more famous friend's help the way some truly terrible filmmakers have from being part on Kevin Smith's list of hangers-on. Instead, he struck out on his own and never had this much heat again.

Left behind: Roger Avary. Jean-Hughes Anglade has continued to work, though mostly in the kind of French projects that don't get wide releases in America. He didn't crossover the way Julie Delpy did.