Romance Week: Let's Get MOONSTRUCK - an ode to the manic pixie dream guy

by Jo Rempel, Staff Writer

Soon after I watched it for the first time, Moonstruck became a fact of life. Maybe it’s because I was entering the peak of my Cage infatuation; maybe it’s because romcoms are rarely imbued with such bombast; maybe it’s because I remain enamoured with Italian-American affectation. By the time I’d seen it for the second time, it had become my favourite film by default, and would go on to become my most-seen.

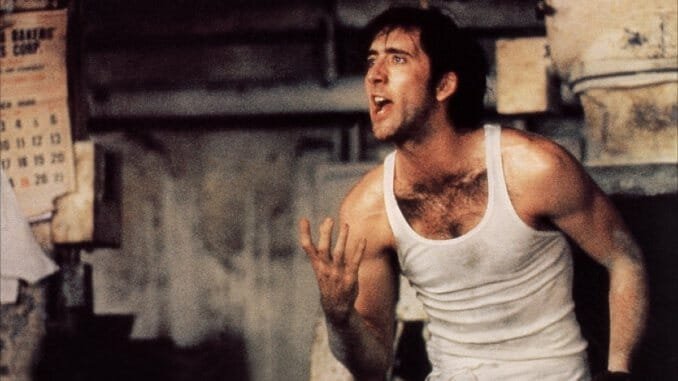

It would be easy to take the film for granted, to assume that its effect has been dulled. It would also be easy to forget what a watershed Moonstruck was both for Cher’s burgeoning career as an actress and Norman Jewison’s directing career, which had been in a lull since Fiddler on the Roof became the highest grossing movie of 1971. Some moments are absolutely burned into my memory: Danny Aiello rubbing at his scalp, Cage shout “I lost my hand!” while visually evoking Metropolis’ mad scientist, Cher saying “in time you’ll drop dead and I’ll come to your funeral in a red dress.” I want to interrogate this love, though. What am I enamoured with? Who are we as an audience meant to be enamoured with?

The object of our, and Loretta Castorini’s (Cher) attention is Ronny Cammareri (Cage), estranged brother to Johnny Cammareri (Aiello), Loretta’s fiancé. This is more than just a tryst; it’s a radical act of self-actualization for Ronny and Loretta. Our perspective on this is rather one sided, with Loretta and her family as the focus, and Ronny as the key to problems she might not have even known she had. “Manic pixie dream guy” is a good place to start when describe his role in this. The manic pixie dream girl has been a rom-com trope since, according to a seminal AV Club listicle, Katharine Hepburn trolled her way into Cary Grant’s love life in Bringing up Baby (1939). The use of the term is loaded to say the least, as things pertaining to women in media go. Nevertheless, manic pixie dream girls exist as a solution to narratives that want a power imbalance to favour the woman: well, what if the man was a boring nerd? Again, loaded terms, but the manic pixie dream guy works off a hard truth: that women’s lives are often themselves boring, are often made to be boring.

It would be unfair to call Loretta trapped by her potential role as wife and mother. She actively values family, and her ability to care for people. There’s no sign that she’ll give up her job(s) as an accountant. Yet it remains that men hold power, even when they do so ineffectually or unknowingly.

When Loretta and Johnny are at dinner together, just before he proposes we’re treated to the first of two disastrous dates between a professor (John Mahoney) and one of his students—two different students, though when their distaste hits its peak, both will decide to splash their water on him and walk out. Johnny chuckles to himself, hand covering his mouth in one of acts of exaggerated self-effacement. “A man who can’t control his woman is funny.” The irony will not be lost to us when Loretta demands he propose marriage properly, on one knee and with a ring. Misogynist values have put blinds over his otherwise soft demeanor.

We can spend hours deriding, critiquing, lauding and subverting the manic pixie dream girl, the archetypical “uncontrollable” woman. This all hinges on the fact that story after story gets pumped out from a singular straight male perspective. That is the baseline. The apotheosis is reached around Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004), most of which takes place in a physical manifestation of Joel’s (Jim Carrey) degrading memory. It’s more likely to see a movie that tips the scales by embodying both sides of the heterosexual couple’s perspective, rather than solely the woman’s. Before Sunset (2004) is an excellent instance of two people mutually manic pixie dream-ing each other. The romance between Hellboy and Liz in Guillermo Del Toro’s Hellboy (2004) is one of my favourites, and Ron Perelman’s gruff manchild would fit the dreamguy bill if this were Liz’s movie.

But anyways, a brief detour into a manic pixie dream guy canon: Clash By Night (1952), a subversive take by ever-cynical Fritz Lang, with classic Hollywood sad sack Robert Ryan as Barabara Stanwyck’s lover; All That Heaven Allows (1955), between rich widow Jane Wyman and bohemian heartthrob Rock Hudson; House of Games (1987), ostensibly a Mamet thriller but really a Mamet romance about a woman awoken from her laser-focus psychiatry career by a hard-nosed con artist; and Priscilla (2023), Sofia Coppola’s magnificent coming-of-age story, full of languid enchantment toward the king of pop. While this is a rather broad swath, all of these begin with women who are trapped by routine, be it at home or at the workplace.

Loretta’s situation is a bit more complicated. As much as she’s able to get what she wants from the start, she’s stuck herself to a man who doesn’t know what he wants. What makes a rom-com work on a fundamental level, at least for me, is self-consciousness. The protagonists must become aware of their own decisions. And when a couple is established, it doesn’t necessarily matter whether the pair are kismet or a disaster waiting to happen: they just have to know who they are. A manic pixie dream girl is self-actualizing from the start, and has to bring the guy up to her level. Ronny Cammareri and characters like him are allowed more leeway in this regard: they are allowed to yearn and anguish with little more than a meet-cute because women are expected to accept the role of emotional carer more easily. In a 1988 interview with Cher, Harlan Jacobson brings up how the core of Loretta and Ronny’s relationship is the empathy she shows for his loss. She forms it into a narrative, which while not generous to him, takes the Freudian approach to accidents by piercing into the unconscious tension, his hatred of commitment and fear of himself. No matter how confrontational, “empathy is not the quality of warriors,” says Jacobson. “It’s what separates men from women. Women have learned it from the cradle on. And it’s the center of the film: you believe in a damaged man.”

Jacobson frames this belief as something of a male fantasy. As for Loretta’s own fantasies, they bolster Ronny’s, if critically. There is the fantasy of planning one’s wedding or dressing up for the opera. There is also the fantasy of being able to tell someone to “snap out of it!” and for it to work.

Loretta is given the most overtly “witty” dialogue, as she’s someone who prefers things concise and direct. Making banter with the mortician while doing his bookkeeping, high off his “artistic genius”: “Then how come you got butter on your tie?” To Ronny, who when offered a steak belligerently requests it well done: “you’ll eat this one bloody to feed your blood.” She speaks with the confidence of folk wisdom—no surprise then, that her first husband’s death was supposedly the consequence of an improper wedding. Ronny, on the hand, is a self-loathing bad boy who loves the opera more than anything. Anything, that is, until Loretta enters his life. This is the magic of the scene where Ronny asks Loretta out to the opera: the bare simplicity as he enumerates the two things he loves. Neither can be possessed, only enjoyed, but wouldn’t he die happy if he could just enjoy them both in the same night. Ronny and Loretta work as a couple precisely because they are fundamentally, uncompromisingly incompatible. Neither has any illusions about that.

As for Moonstruck’s appeal, many will point to the film’s quasi-magical sense of permanence. Cher herself comments to Jacobson on how “there’s a family structure that no matter how it seemed to be weakening or falling apart, it came together in the end—like in a fairy tale.” Writing in the same issue of Film Comment, Marcia Pally picks up on this notion as part of a larger trend of American films that beckon us towards the family. “What’s going on with our projection of the family onto film that we insist on its inevitable niceness?” Once everything is resolved and the whole family is toasting Loretta and Ronny’s engagement, the camera floating behind the doorframe, panning across the family memorabilia, settling on a picture presumably of a young Loretta. Then, a crossfade onto the portrait of the elderly D’Andreamallea couple, proud that the family legacy is carries on. It is undoubtedly saccharine. But with everything preceding this moment, are we to believe these two had it “all figured out?”

If you listen to the DVD commentary track, the convivial ensemble scene was a nightmare to shoot—things are never quite what they seem on the surface, or how you want them to be. Pally says that “over the long haul, we need to share trust, jokes, disappointments, and late-night TV. We need it in spite of all the problems.” Moonstruck does not stray as far from this idea as she makes out: to go further, it desires family because of all the problems. The only way to make it through sometimes is start an argument, and it only well and good to stew in the anguish of falling in love.