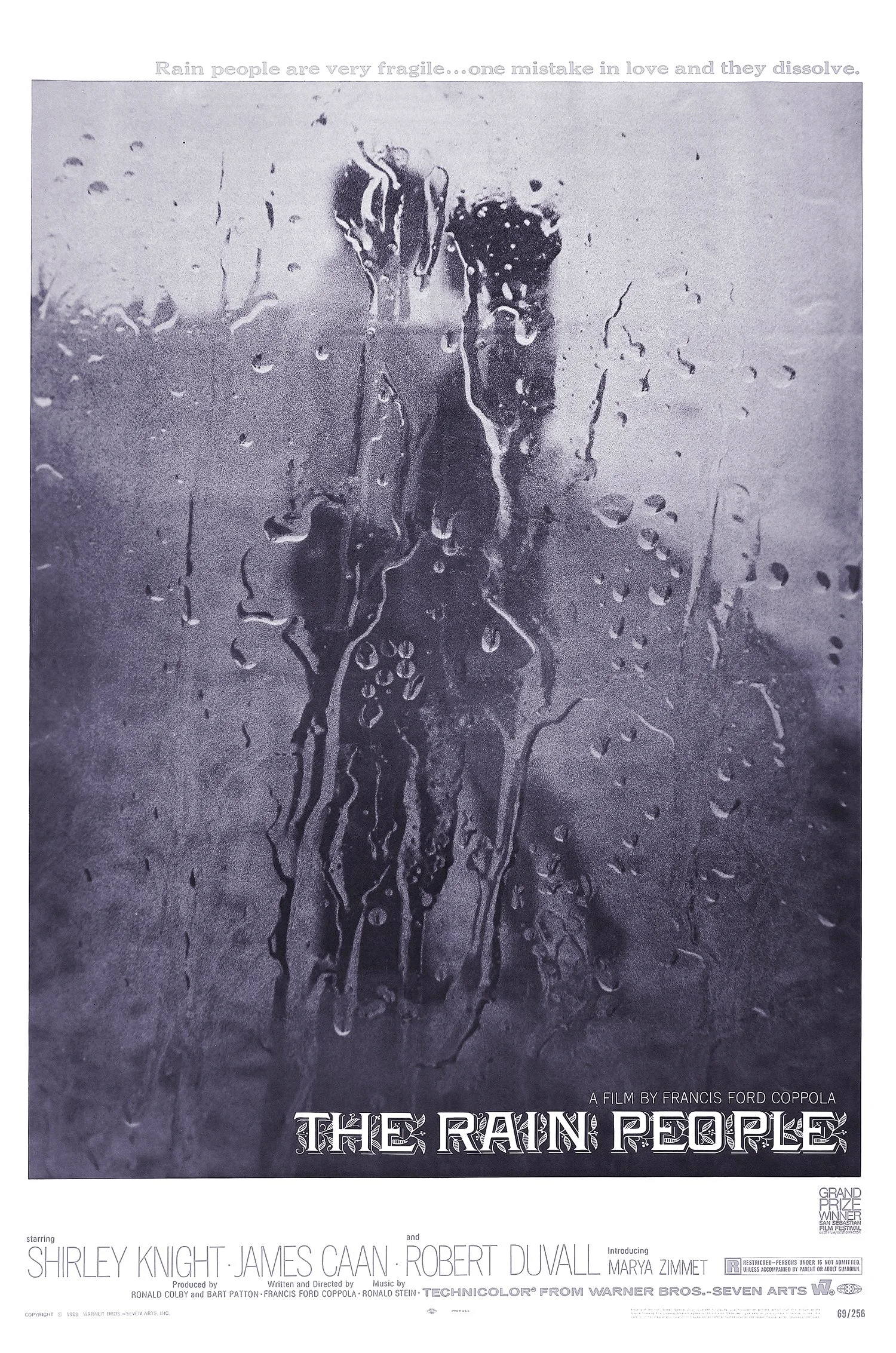

Coppola Week: THE RAIN PEOPLE embodies the transient experience of its shoot

This week, in honor of the wide release of Megalopolis, MovieJawn is looking back at some of Francis Ford Coppola’s lesser-discussed work. No Godfathers, Conversations, or Apocalypses right Now. Read the other articles here.

by Kevin Murphy, Staff Writer

At the end of the 60s, after leaving the tutelage of Roger Corman, Francis Ford Coppola took yet another one of his famous gambles and set out to make a road movie with small stakes. The Rain People, released between the fizzled musical Finian's Rainbow in 1968 and the landmark that would be The Godfather in 1972, is not one of Coppola’s better-known works. Nor, for that matter, does it have the power of his films in the following decade, being a more personal work and closer to the guerrilla-style production of 1967’s You’re a Big Boy Now than it is to anything that Coppola has done since. But it's because of the way in which the film was made, as well as its exploration of two major elements–one thematic and one technical–that it remains an important entry into Coppola’s early filmography.

Coppola intended to depart from the conventional means of making films. In this case, it meant traveling the country using a caravan of vehicles where the crew would live and the film’s footage would be edited. The locations weren’t set ahead of time, and improvisation was key. Much of this was captured by a young George Lucas in a short documentary called Filmmaker, which showed the difficulties in making the film, arguing about financing and working with the director’s guild, feuds between the director and lead actress, and above all else Coppola’s intense devotion to making his movies, the way that he wanted to make them. It’s very enlightening to witness the process, because this movie was made in such a unique way, and the improvisational nature of those methods are reflected in the wandering feel of the final product.

The film is something of a transient experience for everyone, especially the characters. It begins in the middle of the story, with Natalie (Shirley Knight) leaving her husband as we enter our role as witnesses. The opening is a view of a house on a quiet, rainy morning, the trash being picked up. This is a remarkably mundane scene that establishes two things in an instant: first, it sets the straightforward tone of the film, which never leaves its grounded reality despite attempts by its characters to escape; and second, it sets up the audience’s role as a voyeur, peering into someone else’s life in a manner that feels intrusive.

The impossibility of escaping the established roles the characters have is repeatedly shown. Natalie is trying to run away from a life in which she feels trapped, which is made clear shortly after the film starts in a long single-take call to her husband from a highway gas station phone booth. This scene has two lines that are important: "The married lady- she was getting desperate" and "she's pregnant." They reveal so much. Natalie is separating herself from her actions and reasons, as though she isn't allowed to have her freedom, but someone else is. This will come up again when she tells Jimmy (James Caan) that she “just wants to see what a football player looks like without his shirt on" and telling Gordon (Robert Duvall), the cop who pulls her over that she is not divorced. She has lost sight of her identity, being removed from the independence that she once had but not wanting to be the wife (and soon-to-be mother) that she is. The purpose of her journey is a hope for some kind of self-discovery and freedom. However, it is ultimately futile, because she never escapes the role of mother for Jimmy despite several attempts to leave him behind, and remains faithful to her husband despite attempts to break that.

There is little way to resolve this within the span of a film without some shattering incident, and the relative mundanity of what we are shown (again, consider how it opens on a garbage truck coming down the street) hints that this isn't a story with wild turns. We should not expect Natalie to get the closure that she seeks, or that we would normally get as viewers. At the very end, that shattering incident drives home the fact that Natalie can’t escape her reality. Her hope for a revelation goes unrealized, the tragic events of where the film ends pushing her back to the familiar that she wanted an escape from.

The second point is demonstrated on a more technical level, The idea of voyeuristic scopophilia–enjoying watching someone who is unaware of being observed–is very apparent here in how shots are framed and how conversations happen. The artifice feels pointed out, like in works of the French New Wave, rather than having the invisibility of more traditional Hollywood methods. Here, we as the audience are voyeurs overhearing the characters and peering in on the story: in that aforementioned conversation between Natalie and Vinny this is made clear by the way the audio switches from external to across the wires, recorded over the phone. Years before The Conversation in 1974, Coppola was letting the audience spy on his characters. In that later work, however, the audience often spies in ways that seem impersonal–the paranoia the film is validated by the very act of us watching the events. The Rain People presents a more intimate look at the story. Here, we are the telephone operator, able to hear conversations over the wires; we are inside the motel, watching Natalie from the corner; we're looking through the car window as Jimmy tells her his story. In almost every shot, there is something between the camera and the characters, emphasizing the sense of voyeurism. Even when that is absent, it still feels like an intrusion because of framing and use of close-ups, giving us a look at Natalie in bed with her husband, or taking a shower, or focused intently on her face. Even the flashbacks are glimpsed as fragmented and silent, peering through the keyhole of memory.

In this regard, The Conversation is a close cousin to this work. That latter film has multiple scenes that are filmed from the perspective of a camera set up to spy on the characters, who move in and out of frame rather than being smoothly followed. One moment sees Gene Hackman’s character walking off-camera, and with a jerk–as though with difficulty–our viewpoint turns to follow him. Where there is a coldness of the spy to The Conversation, there is a humanity to the way that The Rain People offers the same perspectives. It lacks the professional detachment and functions instead like a nosy neighbor.

The major criticism that I had of The Rain People when I first saw it was its lack of closure; it’s unsatisfying as the ending to a story because it denies us any confirmation of what happens next. Over time, I’ve come to recognize that as inevitable. Whether intentionally or not on Coppola's part, and perhaps because of the improvisational method of filming, the audience was never meant to witness this story to its conclusion. We come into it partway through, and we leave it before it's finished. It doesn’t close the door on us like Michael Corleone does at the end of The Godfather, nor does it offer the peace of stepping into the sunlight at the close of The Outsiders. Instead, the film treats the audience like a hitchhiker, picked up in one part of their journey and dropped off where it's ready to part ways with us, not when their journey ends.