Ryan Silberstein's Top 15 movies of 2022

by Ryan Silberstein, Managing Editor, Red Herring

I enjoy making lists. All kinds of lists. It’s just part of how my brain organizes things. But lists or rankings of art are merely snapshots of how I feel in a particular moment in time. They would be different on any given day, not that I didn’t spend time putting this list together, but trying to pick 15 films I wanted to highlight as the best of the year is an impossible task. So these are my picks, I am sure I left off a lot of other movies people loved, including about a dozen I wasn’t able to squeeze in over the last few weeks.

If there is something shared between all of these movies, it is the question of “Who tells our stories? And what do those stories mean?” All of the films on this list feel extremely personal and could only come from these particular filmmakers and their collaborators. There is also an unintentional bias towards big movies, not based on budget or impact, but stories that feel like they could only be told best in a cinematic format. A list of spectacles, if you will.

That said, any of these 11 honorable mentions (listed here alphabetically) could easily swap in for any of the movies in the 11-15 slots. Links are included for the ones I reviewed here.

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed

Elvis

Fire of Love

Girl Picture

The Northman

Prey

15. RRR (dir. S.S. Rajamouli)

Soaring above Hollywood’s obsession with realism, RRR is packed with mythological and symbolic meaning as well as stunning dance and action choreography. Each sequence becomes a flurry of amazing moments, dazzling across the screen as the music pumps with each beat.

There’s a lot of commonalities with spaghetti westerns in the storytelling, except that the pace sustained here is breathless. Centering on a bromance for the ages, but one destined to be ripped apart by secrets, there is joy, tension, and peril throughout. When the intermission card came up my jaw dropped realizing that the middle act action set piece was not at all the finale. Though the last act never quite rises to some of the more outlandish moments in that sequence, it continues to escalate emotionally until the credits hit.

14. Armageddon Time (dir. James Gray)

Armageddon Time feels akin to 20th Century Women, but from a Jewish-American East Coast perspective. Paul will learn how to become a man, likely from the men and women around him. While Esther and Irving often seem at a loss on how to deal with Paul, his grandfather is the perfect mix of mentor and co-conspirator. From encouraging the boy’s interest in art and model rockets, to sharing the story of how their family escaped Europe, grandparents are often the sharers of secret knowledge, and Paul’s is the perfect example. Irving, meanwhile, is a source of both love and fear, and even hate. Much like my own upbringing, Paul would rather deal with Esther when he gets in trouble. His father has a temper, and is more likely to come after Paul with a belt. But we also see Irving spreading joy, singing a good morning song while banging kitchen utensils to wake his sons. In these moments I was filled with a hope that Paul will be able to close some of the distance between him and his father as he grows up.

13. Decision to Leave (dir. Park Chan-wook)

The second best movie this year to invoke on Mahler’s Fifth symphony, Decision to Leave walks a fine line between parodying soap opera storytelling and being an earnest neo-noir. Park Hae-il plays a detective who is drawn into an accidental death that he does not believe is an accident. In his search for answers, he becomes obsessed with the case as well as the wife of the deceased, played by Tang Wei. What follows is an ouroboros of truth, doubt, manipulation, and heartbreak.

Cinematographer Kim Ji-yong shoots the hell out of this movie, and gives many of the scenes–from apartments to snowy mountain sides–the feeling of tableaus, the characters moving through perfectly arranged spaces. This enhances the juxtaposition of the lead detective’s spiral downward from order to chaos, while also making it a pleasure to look at.

12. Retrograde (dir. Matthew Heinman)

The goals of Retrograde seem two-fold: first, to show the relationship between the US and Afghan forces in Afghanistan as of 2021, and two, to show the immediate aftermath of the US withdrawal. Ultimately, there it succeeds at both, but the first is more revealing. The camaraderie between the Green Berets and the Afghan Major General Sami Sadat as well as the men under his command is touching, especially as the Americans deliver the news of our exit. Seeing not just papers and computers, but perfectly good ammunition destroyed and not handed over to the country’s military is damning, underscoring how much of a waste our 20 year attempted occupation of the country has been. It’s nothing compared to the lives lost, but it’s a perfect metaphor of everything that has been destroyed over the years.

Another salient point in the film concerns the passage of time. There are soldiers on both sides that were in diapers on 9/11. There are members of the Taliban who joined because they had family killed by coalition forces when they were children a decade ago or more. A sense of shame pervades, and only grows as the documentary follows the slow retreat and exile of Sadat. Well worth watching for anyone looking to get a better view of America’s longest war.

11. Avatar: The Way of Water (dir. James Cameron)

This Avatar sequel is Cameron’s victory lap. He’s playing his hits. There’s Cameron returning to mysteries hidden by the ocean (even if this one isn’t ours) for the first time in fiction since The Abyss. The space marine aesthetics of the bad guys are straight out of Alien$. Like Terminator 2: Judgment Day, it’s about warriors and their young kids having to flee an overwhelming threat from a distant place. It’s been a while since I’ve seen True Lies, but there is some relationship drama in here as well. And there is an extended riff on the sinking of the Titanic in the final set piece. Add to that the anticolonial, anticapitalist, and strong environmental themes, and you have a full scale epic that feels as personal as anything Cameron has ever made. There’s a heartfelt earnestness that’s refreshing compared to the “ironic” detached tone of so many other big budget movies at present. There’s no fourth wall breaking smugness, no reliance on pop culture references for cheap humor, and no one trying to protect their star persona behind the scenes.

10. The Woman King (dir. Gina Prince-Bythewood)

Along with Devotion and Till, The Woman King is an old school movie told from a perspective we haven’t ever gotten enough of on screen. The large scale production design and the performances, especially from Viola Davis, Thuso Mbedu, and Lashana Lynch, feel akin to something Cecil B. DeMille or David Lean would have dreamed up. I love new perspectives on classic Hollywood genres, and while it may seem easy to forget why those movies connected with audiences, The Woman King is a great reminder. Plus with the training sequences, Gina Prince-Bythewood shows off her love of athleticism and the way bodies move across the screen so much better than she was able to in The Old Guard.

At the same time, it tries to not shy away from moral complexity. There’s no way to put Africans involvement in the European-controlled slave trade in a simple box, and the film does its best to navigate that while still telling an anticolonial story. While it may not be as great as Lawrence of Arabia, it certainly should be included in the great historical epics.

9. The Fabelmans (dir. Steven Spielberg)

The Fablemans is certainly a deeper look into Spielberg’s psychology through his movies, but at the same time, it feels more revisionary than revelatory. A corrective for his past guilt over his parents. And perhaps it is that, a vanity project, a tribute to himself and his clan. Dismissing it as such is certainly a valid point of view. It seems pointless to argue whether or not he’s earned the right to do this or not, artists should be able to make what they want. But I also can’t deny that certain scenes deeply affected me. It spoke to the ways I view my parents, and how my relationships with them, and my view of them and their marriage, evolved over time. Like Sammy’s, it wasn’t a particularly difficult childhood, but it was mine. I struggled to figure out my own identity until I was living on my own, which is also a common experience. As a fan of the man’s work, it is easy to get caught up in all the trappings, all the specifics. In many ways, Spielberg is the reason I love movies. His films were an easy gateway to discover more and more, a path I am still following today.

8. Mad God (dir. Phil Tippet)

Thematically, if Mad God is about anything, it is about the pain of creation. The most common noise in the film’s soundscape is crying infants. Stop motion animation is a labor of love, especially doing it just for the love of it, but it is a painful labor, time consuming and requiring immaculate attention to detail. It is easy to imagine the metaphorical pain of trying to birth this film over the course of 30 years. Now we get to bask in that vision whenever we want. And you definitely should, after midnight, when it’s quiet and still except for the sound of your existential fears.

7. Women Talking (dir. Sarah Polley)

One of the best, clearest examples of uniting form and theme in recent memory. While Sarah Polley never shows us the absolutely horrific events perpetrated by the men in the colony, it doesn’t need to, either. Mostly set in a barn, mostly just women talking (with a bit from Ben Whishaw), Polley deftly captures the emotional and sometimes contradictory way humans deliberate and decide. The use of closeups as well as the overall blocking is all emotion-first, and that conveys so much even if that woman isn’t the one talking. Each actress gets their own moment where their mind is changed, or something is revealed, each of them like a different voice in a choir. There is no group action without discussion, and figuring out consensus can sometimes be an act of bravery in and of itself.

6. Ambulance (dir. Michael Bay)

Bay’s ideology–a sort of old school neoliberalism that is skeptical of institutions and is enamored with the idea of one person doing what they know is the right thing in the face of what they are supposed to do in that situation–is almost entirely driven by class consciousness that makes him stand out from most other white male American filmmakers. While it would be easy to say that Bay is merely expanding “snobs vs slobs'' into a political ideology, it is fascinating to see who is good and bad in this morally gray thriller. Will, a former solider, and Cam, as a paramedic, are shown as constantly heroic. Will’s service got him out of the life that Danny leads, and Cam’s dropping out of med school shows her to be exceptionally competent and hard working. How Bay sees Cam is perfectly contrasted during a sequence where she has to call some doctors for help. They are in nice upper middle class homes or on the golf course, distant and detached, reaping the benefits of their privilege while Cam thrusts her hands into open wounds in the back of a moving vehicle. Bay is almost equally skeptical of police as an institution, and the script implies several times that the cops endanger lives with their tactics, more concerned with trapping the bad guys than protecting and serving. This seems like a good time to remind you that in Transformers, the cop car is a Decepticon.

5. Everything Everywhere All At Once (dir. Daniel Scheinert, Daniel Kwan)

One thing The Daniels’ concept of the multiverse allows for is characters borrowing skills from alternate universe versions of themselves. So from a universe where Evelyn stayed in China and became a martial arts devotee/actress, the laundromat-owning Evelyn can gain a deep knowledge of kung fu. Or from other universes, singing skills, hibachi knife-work, etc. Through this Evelyn is exposed to wildly different versions of herself, each shaped by a series of choices that she could have made but didn’t. In The Daniels’ multiverse, we are the culmination of our own choices. It may seem that on the surface, the multiverse is about exploring all of these different paths, but it is actually the opposite, it is about The One (not to be confused with the Jet Li multiverse movie)–the Unified Theory of Evelyn.

It would be totally reasonable to react to the multiverse by saying that ‘nothing makes sense, nothing matters,’ which is ultimately how Joy (Stephanie Hsu), Evelyn and Waymond’s daughter, reacts to her knowledge of the universe. In a field of unlimited possibilities, why does anything have value? The answer is to invert the question. In a field of unlimited possibilities, the particulars of the life we have matter even more. Accepting our past choices is a form of self-acceptance. It doesn’t mean that we are stuck with those choices permanently, but those choices all carry weight and shape the particular versions of ourselves as shaped by circumstantial and systemic conditions as well as our own free will.

The above is from my article “Multiverses and Madness All At Once: How an indie film beat Marvel at their own game” here on MovieJawn!

4. Top Gun: Maverick (dir. Joseph Kosinski)

A parable of the Last Real American Movie Star.

What I love about this movie is that Maverick doesn't fly for himself. He flies for others. At the beginning of the film, when he takes an experimental plane over Mach 10, it's not because he's showboating. It's to save the jobs of all of the people supported by the program. And when Tom Cruise, movie star, hangs off the side of a plane or rappels off the Burj Khalifa, it's because movies–as noted in the end credits–create thousands of jobs and pay for hundreds of thousands of hours of labor to exist. Tom Cruise puts his life on the line for us, the audience, so his movies can pay to keep the industry going.

He's always been known as a cinephile more than most stars, and watches at least one movie a day. His hit rate is remarkably steady, with Lions for Lambs is most notable disappointment as a star since 1992 (in my house, we like The Mummy), and so Cruise continues to be a reliable source of quality.

That's how it works for Maverick in the Navy as well. In the film, Mav is brought back to Top Gun school alongside more recent grads so he can teach them how to do the trench run from the end of multiple Star Wars movies. Maverick is a relic of another time, and in his spare time, works on a P-51 Mustang, a World War II fighter plane. We're nostalgic for the 80s, when things were supposedly better, Maverick longs for being an ace in the 40s, perhaps. We crave 80s movies, Cruise looks back to the studio system when stars were the main attraction. It's cycles of nostalgia.

But this movie kind of subverts that. It's not quite "let the past die, kill it if you have to," but the main theme of the film is to let go of the past. The rift between Maverick and Rooster (Goose's son, played by Miles Teller with an Anthony Edwards mustache) is from a past incident. Ghosts haunt both of them and keep them from finding their true potential. The Navy favors unmanned fighters, Maverick continues to demonstrate how humans are able to push the limit in expensive taxpayer-bought super machines. But while the writers come up with a reason for this mission to be run in human-piloted F-18s that were retired from service in 2019, there's a pervasive sense throughout that this is the 'one last job' for human pilots, giving it a melancholy twinge that works to help you revel in the sheer power of the sounds and image bombarding across your senses.

Kosinski does pay tribute to Tony Scott, with the latter's editing and affinity for sunsets on full display. I smiled every time the fighter planes accelerated, held my breath when they stalled, and felt.a cheer rising up when characters seemed to beat the odds.

Tom Cruise is always worth showing up for because he always shows up for us. His star power is making charges that his body seems to have an unlimited line of credit to draw on.

3. Aftersun (dir. Charlotte Wells)

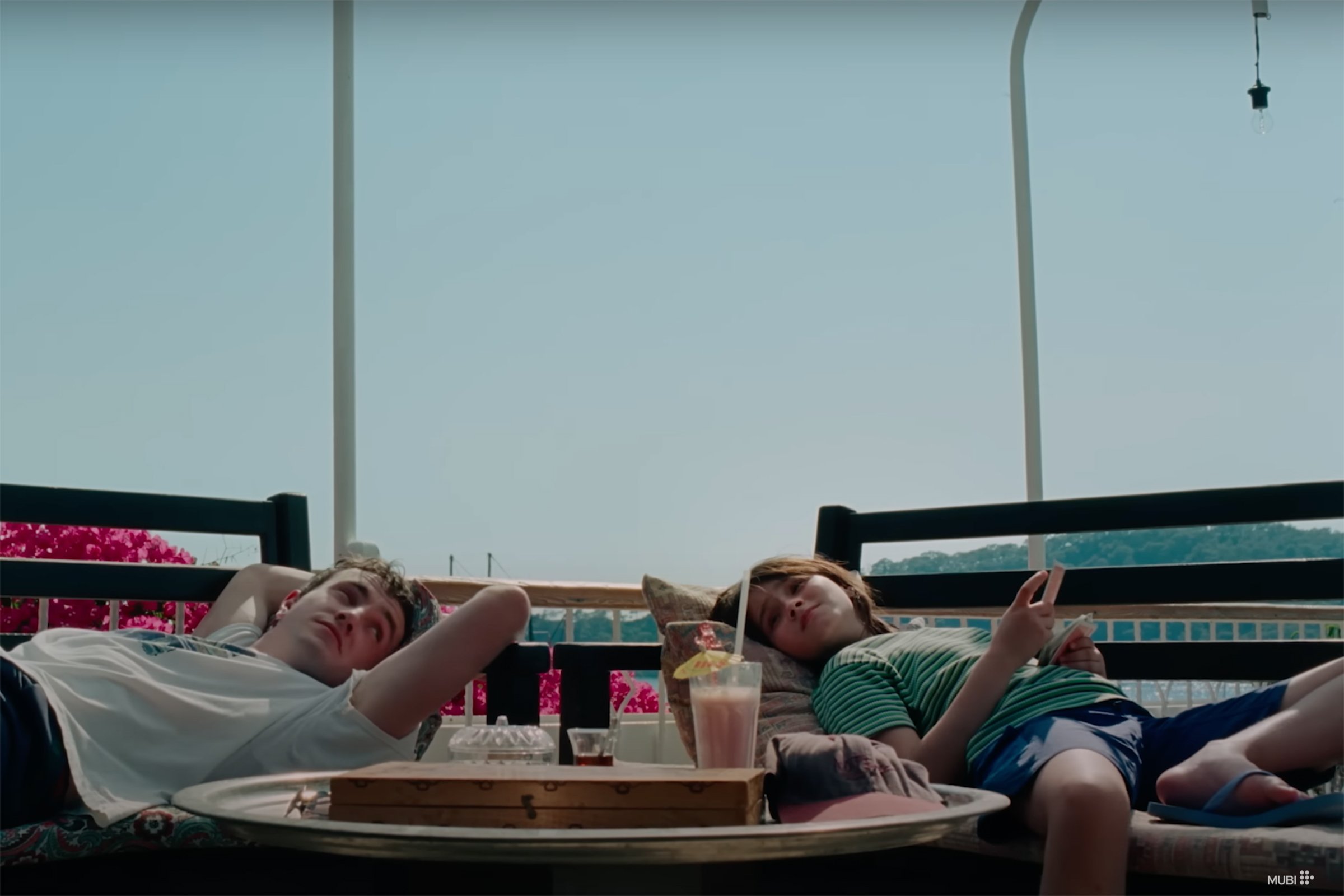

One of the scariest concepts about parenthood is not knowing what memories will imprint on a child. Could it be a grand gesture, an expensive vacation or a toy? Is it something smaller, more innocuous, like a quiet moment or conversation? Or is it a moment where they discover their parents are flawed and fallible? Memory is the core subject Charlotte Wells interrogates in her impressive feature film debut. The tension and fragility of the relationship between Sophie (Francesca Corio) and her father, Calum (Paul Mescal) rises and falls over the course of their stay at a resort in Turkey. He seems to only see her once a year, but what is clear is that he seems like a young lost dad. Calum is mistaken for her older brother, money is tight, and he shows classic signs of depression. Sophie, aged 11, is right on the cusp of becoming a teenager. She is self-actualizing, observing older kids intently, trying to understand their social cues and relationships. But he still has a strong bond with her dad as they spend their holiday by the pool and taking in what the resort has to offer.

The film’s opening is shown from the videos that Calum and Sophie recorded on this trip, and the present day Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall) provides an infrequent but haunting presence throughout the film. Wells’ direction occasionally seems elliptical when it lingers on a moment longer than expected, but serves the memory-oriented mode of storytelling. By the end, she has constructed a softly devastating portrait of this relationship. Wells reminds us that “it’s the terror of knowing what this world is about,” with a sob-inducing needle drop. The most we can do is hold onto our important memories and try to understand the people we love.

2. Tár (dir. Todd Field)

Control is Lydia’s core personality trait, and Field shows this more than tells us. The way she controls all of her interactions, like inviting people into her office for meetings to show power, or meeting with Andris at a restaurant where they have equal footing and are away from anyone who might contradict Lydia’s version of reality. Sebastian is the other exception, where she attempts to use his office to butter him up, before striking and retreating just as quickly. She leaves him devastated and walks away, asserting her power in his space. Lydia is also shown to be fairly germaphobic, even throwing out clothes that have been exposed to objectionable substances (since Tár acknowledges the existence of COVID, the repeated use of hand sanitizer could go either way). But her biggest problem is with noise. For someone so consumed by music and control, noise may be her biggest enemy. At one point, Andris mentions Arthur Schopenhauer’s theory linking noise intolerance with genius, which actually points back to Lydia’s own self-mythology. But there are a ton of details around this throughout the film, and as Lydia’s anxiety gets worse, so does her sensitivity. My favorite example is how bothered she is by a new rattling her previously near-silent electric car begins to make. Many films are enhanced by close viewing, but Tár definitely exposes so much of Lydia through visual information that distracted watching will severely limit its impact.

1. Nope (dir. Jordan Peele)

Nope is very much a western, in the same vein as so many John Carpenter, Steven Speilberg, and James Cameron movies are built on the foundations of the genre, but relocating their stories to other environments and other time periods. Of course, the western, and specifically the cowboy, is pure mythology; the popular image of the cowboy is that of a white man, but they were just as often Black or Latino. The Haywoods have a real ranch for wrangling horses. But their neighbor, Ricky "Jupe" Park (Steven Yeun), owns a fake western town called Jupiter’s Claim. This fake town is as artificial as our cowboy mythology, but where tourists (hopefully!) know the town is fake, they also likely accept traditional westerns as based on fact. And this all comes back to spectacle. Audiences think we want our fantasies delivered as realistically as possible, but in reality we just want them to have a veneer of realism plastered over our preexisting notions. One of the things that makes Peele such a gifted filmmaker is that his films are pointed without being overtly accusatory. They challenge the audience by whispering in their ear while distracting them with heart-pounding suspense.