“Do you miss me, Miss misery?”: A look back at AS GOOD AS IT GETS and GOOD WILL HUNTING 25 years later

by Sam Morris, Staff Writer

I graduated from high school in 1997. As someone who came of age in the 1990s, I can confidently say that, from a cultural perspective, we did not have good conversations about mental health. Of course, that isn’t to say that we’re having particularly great conversations now, but the internet has brought about patient-centered communities that have managed to shift the popular discourse about mental health to some degree. While mental health parity laws—laws that require mental health treatment to be covered by insurance companies in some of the same ways as other health treatments—did exist in some states in the 1990s, they proliferated rapidly in the 2000s. I’ve learned a lot about mental health since we left the 1990s behind; however, like many, my initial beliefs of what mental health and mental illness were have been formed in large part by popular culture. Two films, both released in December of 1997, were seminal in the construction of those beliefs: As Good As It Gets and Good Will Hunting.

These films couldn’t be more different from a narrative perspective. As Good As It Gets is a comedic film that centers on a curmudgeonly writer who is forced into relationships with his gay neighbor and a single mother. Good Will Hunting is about a genius from the “wrong side” of Boston who is mentored by two college roommates, one a professor at M.I.T. and the other a psychologist who teaches at a community college. Both films, however, rely on depictions of mental illness in their protagonists to create compelling stories. Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson) has untreated and uncontrolled obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and Will Hunting (Matt Damon) is an abuse survivor who is unwilling to seek treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

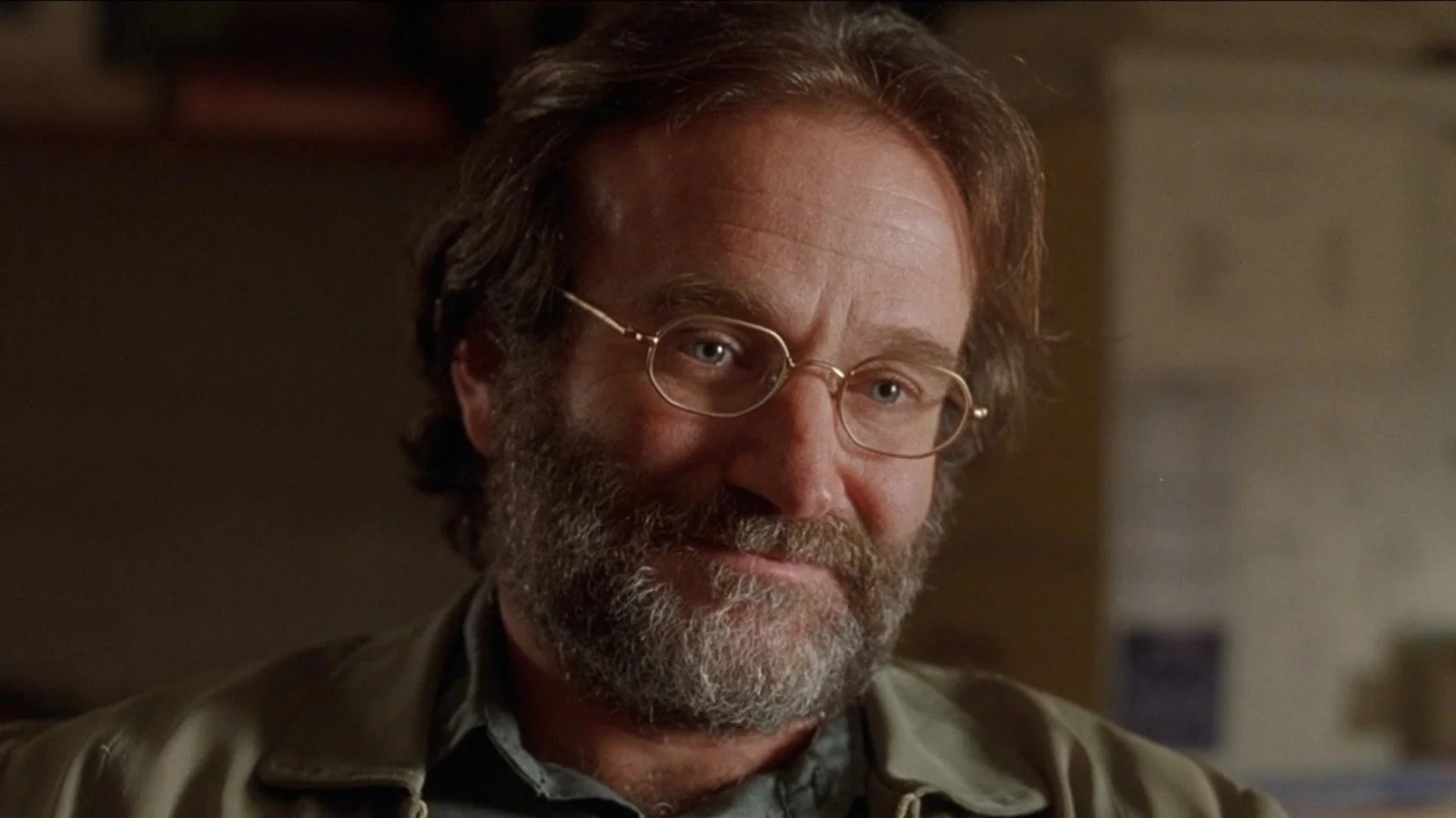

Despite being overshadowed by Titanic, As Good As It Gets and Good Will Hunting both did very well at the 70th Academy Awards. Jack Nicholson and Helen Hunt took home both lead acting awards, while Matt Damon and Ben Affleck won for Best Original Screenplay. As far as I’m concerned, though, the best moment of the night—the first Academy Award ceremony I ever watched—was when Robin Williams won the Best Supporting Actor award for his portrayal of Will Hunting’s therapist. Along with L.A. Confidential and The Full Monty, the 1997 slate of Best Picture nominees were truly movies that “regular people” had seen. As such, they both played into and shaped narratives of mental illness and mental health. While both are a far sight better than Rain Man (1988) and What about Bob? (1991), these two December 1997 films are still playing into existing tropes of mental illness.

When I first saw both of these films in early 1998, I enjoyed them both and have seen them many times since. Good Will Hunting remains one of my favorite movies. Looking back on these films twenty-five years later, I see them as interesting artifacts of the late 1990s, but I also see them through a different personal lens. In 1998, I hadn’t yet been diagnosed with OCD, and I was also not yet an abuse survivor dealing with PTSD from a decade of intimate partner violence. Neither of these films is perfect by any means—they are far too centered on the experience of straight white men, for one. What As Good As It Gets and Good Will Hunting both try to do with varying degrees of success, however, is attempt to demonstrate the importance of awareness and treatment of mental illness as well as what effects empathy can have on people who are dealing with trauma and/or mental illness.

As Good As It Gets features a gay artist named Simon (Greg Kinnear) who is brutally beaten during a robbery. With help from his agent Frank (Cuba Gooding Jr.) and some newfound friends, Simon works to regain his shattered confidence and artistic point of view. The film also features a waitress named Carol (Helen Hunt) who struggles to make ends meet while caring for her asthmatic son. Carol and her son find their lives improved when a mysterious benefactor sends a caring doctor (Harold Ramis) to the home. There’s enough story here for two entire films, yet neither Simon nor Carol is the main character of As Good As It Gets. That honor goes to Melvin Udall (Jack Nicholson), a racist, homophobic, misogynistic man who happens to be a bestselling romance author with OCD.

Take the average person’s perception of what OCD is, and that’s what Melvin’s life resembles. His day is dominated by rituals and patterns: he locks the door in an elaborate manner, won’t step on sidewalk lines and cracks, and brings his own silverware with him when goes out to eat breakfast, which he does at the same restaurant every day. Melvin refuses treatment because he does not trust the pills that his doctor has offered to prescribe to him, calling them “dangerous.” Meanwhile, Melvin does everything possible to alienate everyone, with the one exception of the woman who brings him his breakfast. When the assistant at the front desk of Melvin’s publishing house asks him how he writes such relatable women characters, he replies, “I think of a man, and I take away reason and accountability.” Director, writer, and producer James L. Brooks paints the picture of a man who willingly walls himself up behind his mental illness; he is a man to be pitied, but not liked.

Except, of course, Melvin doesn’t want to live that life. When Frank brings Simon’s dog, Verdell, to Melvin’s apartment, Melvin seems aghast, annoyed, and angry. Almost instantly, Melvin and Verdell become best friends. Despite the fact that Melvin terrorizes everyone at the restaurant on a daily basis and only narrowly avoids a ban because of Carol’s patience, he sends a doctor to Carol’s house the moment he discovers that her son is sick. Sure, he says he only does that because it’s the only way to get Carol back to the restaurant, but the audience is slowly beginning to get in on what Brooks is doing. Melvin is a bitter man, which is certainly bad enough all by itself. The real villain of the film, of course, is OCD. After arranging a road trip with Carol and Simon so that Simon can ask his parents for money, Melvin takes Carol to dinner. After he nearly ruins the evening (which he eventually does anyway), Carol demands a compliment. Melvin obliges, telling her that he has started taking the pills for his OCD. When Carol asks how that is a compliment, Melvin replies, “You make me want to be a better man.”

Years earlier, Brooks won Academy Awards for Picture, Director, and Screenplay for Terms of Endearment (1983). For his role in that film, Nicholson won Best Supporting Actor. Brooks’ next film, Broadcast News, didn’t win any Oscars, but was nominated seven times. On the small screen, Brooks created, wrote, and produced Rhoda, Lou Grant, and Taxi. He also worked with Tracey Ullman on her eponymous show, which put him in a position to help develop an obscure, niche family show entitled The Simpsons. Simply put, Brooks knows how to mix drama and comedy, create rich casts of characters, and make an overstuffed plot not seem so…well, overstuffed. Unfortunately, by 1997, Brooks was still working on projects that are often described as having “broad appeal”—though I find the broadness of that popularity outside of certain demographics questionable.

As Good As It Gets is painted with such broad strokes that it cannot possibly avoid feeling hopelessly dated. Kinnear’s depiction of queerness would fit right in over at The Birdcage. Melvin’s prejudice is played for laughs in the way that only a 1990s audience could appreciate: forward-thinking enough to be able to talk about out loud but backward enough that audiences pat themselves on the back as if watching Jack Nicholson pretend to be a terrible person is going to solve all of society’s ills. I remember associating OCD with counting, tics, and odd personality quirks, so Melvin confirmed those associations. I imagine that many other people had their assumptions about OCD confirmed as well.

Although Melvin’s success as a writer isn’t a major factor in the film, that success confirms a popular mental illness trope: a person with a mental illness (or a disability) such as OCD who also has some special talent or skill—known as a “supercrip.” These hyperbolized, simplistic characterizations of mental illness rarely do much good, but they do have multiple negative effects. One of those negative effects is the person who says, “Oh, that’s just my OCD,” despite never having been diagnosed. (Not that medical diagnosis is the gold standard it’s made out to be, of course, but being a micromanager or a “neat freak” does not someone with OCD make.) Second, someone who might actually have OCD will see an outsized depiction such as the one in As Good As It Gets and think, “Well, that’s not me,” and then proceed to never seek help for a disorder that can be anywhere from mildly annoying to entirely debilitating.

As Good As It Gets may not hold up twenty-five years later, but it is extremely quotable. My favorite quote comes from Melvin during the road trip: “Some of us have great stories, pretty stories that take place at lakes with boats and friends and noodle salad. Just no one in this car. But a lot of people, that’s their story. Good times, noodle salad. What makes it so hard is not that you had it bad, but that you’re that pissed that so many others had it good.” While Carol and Simon disagree with Melvin, I can’t help but find some truth there. In Good Will Hunting, for example, Affleck and Damon are interested in getting at the heart of what has kept Will from being some version of the person that many people around him think that he could be.

Gus Van Sant’s path to his 1997 award-winning film is far different from James L. Brooks’ path. Having achieved notoriety for Drugstore Cowboy (1989) and My Own Private Idaho (1991), Van Sant found himself working with Nicole Kidman on To Die For. (Interestingly, To Die For features Joaquin Phoenix, younger brother of Idaho star River, as well as Casey Affleck, who appears alongside his brother in Good Will Hunting—small world!) With a script that may or may not have been doctored by William Goldman and an assist from Kevin Smith, Good Will Hunting ended up at Miramax where He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named connected Van Sant with Affleck and Damon. This pairing of director and writers yields a film that has some grounding in independent film but bears the clear watermark of a late 1990s Miramax film. It’s a film that has the gravitas that Stellan Skarsgård and Robin Williams can bring to a film but also a naive sincerity provided by Affleck and Damon.

Will Hunting is a young man from Southie, the “wrong side” of Boston. He works as a janitor at M.I.T. but is discovered to be a genius after solving supposedly unsolvable math problems posted on a chalkboard outside of a classroom. After being arrested following a brawl, Professor Gerald Lambeau (Skarsgård) gets Will released on the condition that he works with Lambeau on math and with therapist Sean Maguire (Williams) on his anger issues. Eventually, Will and Sean develop a rapport as Sean is able to encourage Will to talk about the abuse he endured as he grew up in the foster system. They talk through the ways in which his childhood and subsequent PTSD prevent him from forming relationships with other people—except for his best friend and fellow Southie kid Chucky (Affleck). This inability to form relationships keeps Will from finding a way to use his genius as well as prevents him from developing a bond with medical student and would-be love interest Skylar (Minnie Driver). The film ends with Will leaving Boston, driving toward an uncertain future (to the tune of Elliott Smith’s “Miss Misery.”)

While this film has its faults—again, it’s very white, and it relies a bit too much on the tortured genius trope—I think it holds up much better than As Good As It Gets. The conception of Good Will Hunting is one of my favorite Hollywood mysteries: How did Jason Bourne and Daredevil/Batman come up with such a compelling story? The writers and their director begin by using the audience’s assumptions about how a poor kid from the wrong side of town is likely to act. That assumption is contradicted by Will’s math skills, but then it is almost instantly verified when he ends up before a judge for assaulting a police officer. Professor Lambeau can only see Will for his brain and that brain’s potential. Skylar sees him as a charming, rough-around-the-edges person with whom she could fall in love. For all that, though, the audience is left to wonder—who does Will Hunting think he is? Gradually, through his work with Sean, we learn that Will thinks that he is nothing. Perhaps not nothing, but certainly nothing of note. That’s what abuse can cause someone to think, and the scars of abuse (figurative scars or, in Will’s case, literal ones) stick around long after the abuse ends. Trauma creates and/or changes cognitive pathways; it literally changes how the brain processes information.

Sean has to prove to Will that he’s trustworthy, which he does by revealing that he also grew up in Southie. Additionally, Sean confides in Will that his wife died from cancer years earlier, which Will correctly identifies as the reason for Sean’s own stagnation. When Will finally opens up to Sean, we see past the hard shell that his childhood has forced him to build. For his part, all Sean can do in this moment is repeat, “It’s not your fault.” More than anything else, this scene is what won Williams his Academy Award, and he deserved it. It’s a scene that wrecked me the first time that I saw it, and it still does today. All that said, would any of these people have cared about Will and his trauma if he wasn’t a genius?

Survivors of abuse often have a difficult time believing in their own worth. Why would someone treat me the way that they did if I mattered to them? Will pushes Skylar away because he can’t make sense of her interest in him. She correctly accuses him of being afraid and tells him that she wants to try anyway. Throughout the majority of the film, Chucky doesn’t acknowledge that he is the least bit aware of Will’s trauma; near the end of the film, however, when he sees Will throwing everything away that he has gained from Professor Rambeau, Sean, and Skylar, he tells his friend, “You know what the best part of my day is? It's for about ten seconds when I pull up to the curb to when I get to your door. ‘Cause I think maybe I'll get up there and I'll knock on the door and you won't be there.” The film ends when Chucky gets his wish. There is no telling what happens when Will gets to wherever he’s going, but that doesn’t matter. It’s the trying that counts. As Sean tells Will, "You'll have bad times, but it'll always wake you up to the good stuff you weren't paying attention to."

1997 was a good year for Hollywood, and the Academy Award ceremony the next March is quite memorable. Vanity Fair called it the “biggest Oscars ever.” Elliott Smith did look a little out of place while performing “Miss Misery,” but that could have been because he was sandwiched between Trisha Yearwood and Celine Dion. Again, we weren’t having the best conversations about mental health in the 1990s; As Good As It Gets and Good Will Hunting aren’t the most nuanced in their depictions of mental illness, but at least they were trying. Yes, As Good As It Gets may have done more harm than it did good, and Good Will Hunting relies too heavily on the tortured genius trope. Then again, neither one of them is remotely close to the nadir of terrible representation of mental illness and genius in film: 2001’s A Beautiful Mind. In 2026, I’ll be very surprised if anyone is attempting to valorize that particular film.