Romance Week: The Widening Lens of Queer Romance

by Megan Bailey, Staff Writer

Now that it’s almost Valentine’s Day, it’s time to talk about romance! And I want to talk about LGBTQ+ romance on screen. Over time, the lens of queer romance—that is, who it’s about and the storylines shown—has widened. In earlier days, white people were most often the main characters, and coming out was often the focal point of these films.

Starting with films like Desert Hearts (dir. Donna Deitch, 1985) and Maurice (dir. James Ivory, 1987), the focus was on white main characters who fell in love with other white people, like a lot of mainstream romances at the time. They did ultimately have happy endings for the queer characters, which is pretty revolutionary for the time. The novel, Maurice, is one of the first gay novels to have a happy ending, and it was only published in 1971, after E. M. Forster died.

Desert Hearts was also based on a novel (Desert of the Heart by Jane Rule), first published in 1964. It was one of the first books about lesbians to be published in hardcover, unlike the lesbian pulp novels of the time. Screenwriter Natalie Cooper changed the story quite a bit for the film. She simplified the story by removing subplots and side characters and focusing on the relationship at its heart.

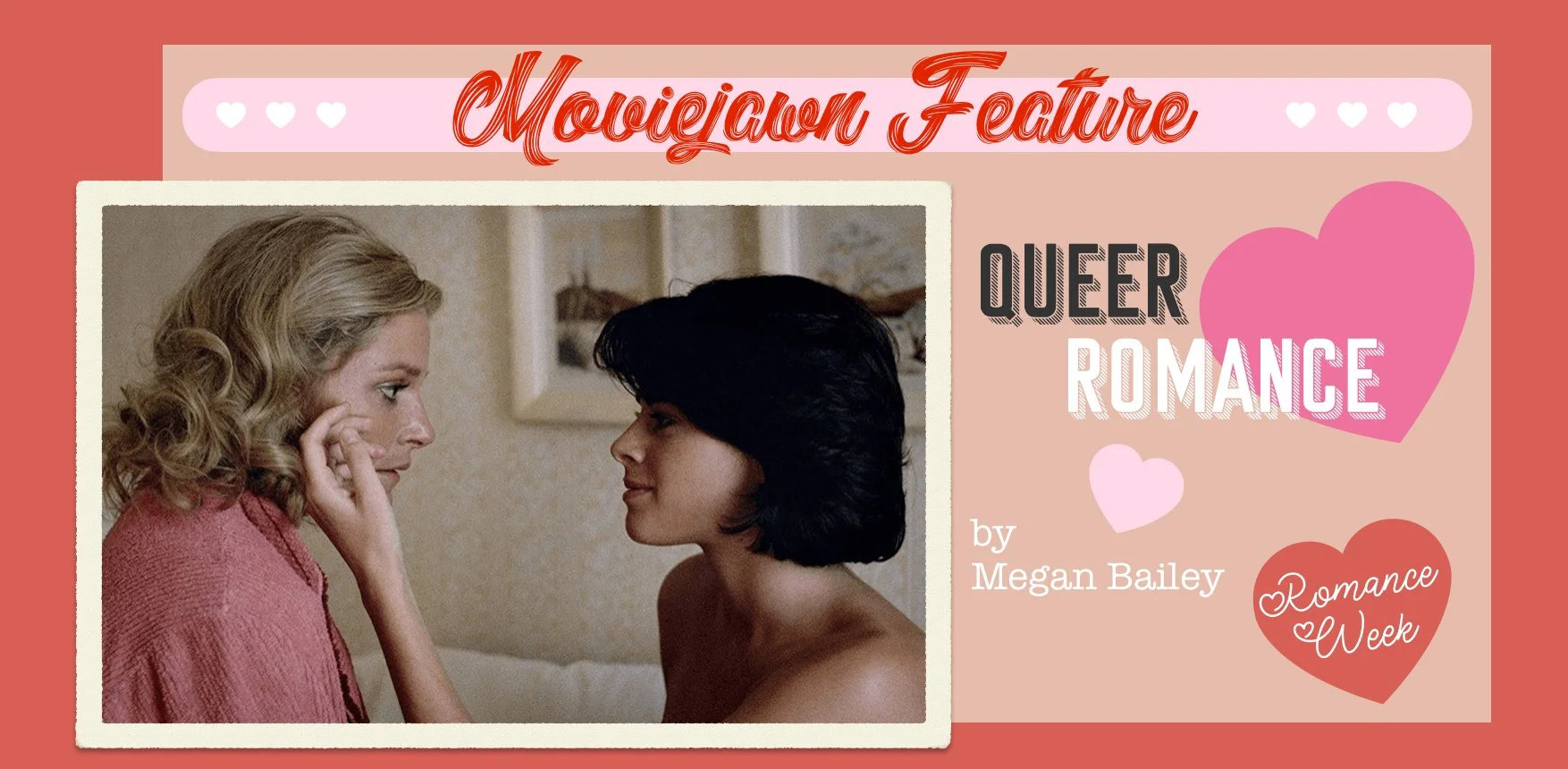

In the film, we follow Vivian (Helen Shaver) and Cay (Patricia Charbonneau). Vivian has come to Reno to finalize her divorce from her husband. She wants to live her life as she wants to, without a husband. He wasn’t terrible to her; she just wasn’t happy in the marriage. While in Reno, she meets Cay, and quickly discovers that Cay has dalliances with women. The two strike up a friendship, and then more, culminating before Vivian is supposed to leave town to return to her normal life.

While this movie is undeniably about coming out, it’s more about acceptance of the self. Vivian needs to accept her own desires as normal, and let herself have what she really wants. In contrast, Cay wants her mother figure, Frances, to accept her. She doesn’t much care about what anyone else thinks. This film is regarded as one of the first films with a positive portrayal of a lesbian relationship, making it a formative film in the queer media landscape.

Notably, the lens of queer film expanded a bit in the nineties to include The Watermelon Woman (dir. Cheryl Dunye, 1997), featuring a Black lesbian main character. It was the first film directed by a Black lesbian, and Dunye wrote, directed, and starred in the film. There was also But I’m a Cheerleader (dir. Jamie Babbitt, 1999), which became a cult classic.

Moving forward to the millennium, we can take a look at Big Eden (dir. Thomas Bezucha, 2000), which is also only partly about coming out. Henry (Arye Gross) returns home to Montana from New York City after finding out his grandfather, Sam (George Coe) had a stroke. Henry wants to come out to his grandfather, but he’s afraid. Of course, his grandfather already knows, and they have a touching conversation about shame. Over the course of his return, Henry reconnects with his childhood crush, Dean (Tim DeKay), but eventually realizes there’s nothing there. He meets Pike (Eric Schweig), an Indigenous man who runs the local store and starts cooking for Henry and his grandfather. What’s so charming about this movie is that everyone in town comes together to make sure Henry is happy. And likewise, the townspeople want to take care of Pike as well. They conspire to get the two men together and celebrate when they’ve reunited at the end of the film. There’s clearly no judgment here, no homophobia. But Henry was scared anyway, as LGBTQ+ people often are when faced with coming out.

Later on, Saving Face (dir. Alice Wu, 2004), again shows the widening lens of queer romance. Focused on Wilhelmina (Michelle Krusiec), a Chinese American woman, who is out to her friends but not her mom. Tragically, this would be Wu’s only film for over a decade, until Half of It came out in 2020.

Of course, the biggest gay movie of the 2000s was Brokeback Mountain (dir. Ang Lee, 2005). While it’s not a main focus of this piece, I do think it’s important to mention the response it got, being branded as “the gay cowboy movie,” often through gay panic “jokes.” However, Heath Ledger refused to make a joke about the film, even at the Oscars. According to Jake Gyllenhaal, Ledger said, “It’s not a joke to me – I don’t want to make any jokes about it.”

In comparison, Call Me By Your Name (dir. Luca Guadagnino, 2017) did not face the same judgmental “jokes” twelve years later . It definitely wasn’t as big of a success as Brokeback, but I do think it says something about where we culturally were in 2005 and 2017 to note the difference there. On the other hand, Call Me By Your Name did face more criticism from inside the queer community in terms of representation and depiction.

Rewinding the clock a bit back to 2011, let’s consider Weekend (dir. Andrew Haigh, 2011). This film features two white British men, Russell (Tom Cullen) and Glen (Chris New), who have very different views on being out and proud. Glen is more politically motivated but vocally not interested in relationships. Russell grew up in foster care and was never able to come out to his family. Glen, roleplaying as his father, gives Russell the chance to come out. Over the course of the weekend, the two bond before Glen leaves for America. The contrasting views of queerness and being “out” are an interesting view on how the LGBT community was split at the time (and still is to some degree). There’s assimilation, or Russell’s simply existing in silence, and then there’s the out, proud, and loud approach that Glen favors.

Further on in the 2010s, it feels like LGBT+ films stalled out with coming-out narratives that spent more time on how the other characters in the film felt it than about the main characters themselves. Jenny’s Wedding (dir. Mary Agnes Donoghue, 2015) is one such example. The film focuses way more on how people react to Jenny (Katherine Heigl) and her fiancée, Kitty (Alexis Bledel) than about their relationship or why they even want to get married. Happiest Season (dir. Clea DuVall, 2020) falls into this same trap.

Of course, Moonlight (dir. Barry Jenkins, 2016) was the big queer film of the decade, and it also shows the widening lens. It featured three actors as Chiron—Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Tevante Rhodes—all delivering incredible performances at different stages of the character’s life. Ultimately winning the Oscar for Best Picture, it was the first LGBTQ+ film with an all-Black cast to win. And this film opened the doorway for more queer films focused on people of color.

Love, Simon (dir. Greg Berlanti, 2018) focuses on Simon (Nick Robinson), a closeted kid in Atlanta. After an anonymous post about a gay guy at his school (who goes by Blue), he reaches out and the two bond. His identity is revealed, leading to Simon being forced out to his friends and deciding to come out to his family, but Blue remains anonymous. This film gets a lot of criticism within the queer community for its “I’m just like you” approach. For me, though, there’s enough character and heart in Simon and Blue (Keiynan Lonsdale) that it’s easy to love and root for them. A good chunk of the marketing focused on Simon’s sexuality and fear about coming out. There’s even a scene in the movie portraying Simon’s straight friends coming out as straight to their parents. It’s goofy, and while it fits within the flick, I get why it was off-putting to other queer folks when used in the UK trailer.

Since 2020, the lens has widened even more, beyond white cis main characters who are constantly coming out. As evidenced with films like Fire Island (dir. Andrew Ahn, 2022), where not only is everyone out, but the focus is simply on finding the right person. These are stories that should have always been told but are finally getting their day in the sun.

Fire Island is a Pride and Prejudice retelling on the titular Fire Island. Starring a primarily Asian American cast, the film follows Noah (Joel Kim Booster) and Will (Conrad Ricamora) as the respective Elizabeth Bennett and William Darcy characters. Noah goes to Fire Island with his friends, and they try to save the house they go to every year. By this summary alone, it’s clear that these friends are not worried about coming out, but they are worried about fitting in in the community. The main characters are all queer men with different perspectives on their sexuality and position in the world. By depicting so many gay men in one film, it allows for more than just one experience to be shown on screen.

There are so many more queer romances, and films in general, out there, but I think it’s interesting to look at how things have changed even since the ‘80s. We’ve gone from Desert Hearts to flicks like Fire Island. There are so many ways to be queer and to fall in love, that it’s only right to have films depicting a number of different experiences. I’m all for the widening lens of LGBTQ+ films, and I hope it only gets bigger.